Exhibit Curated and Digitized by Noelle Beverly

Black Portraiture and Legacy

A portrait represents visibility and remembrance. Whether a likeness is captured in a painting or a photograph, that image offers an opportunity for an individual to be acknowledged, admired, and ultimately, remembered through time. Writing in 2023, artist and author George McCalman argued that portraiture “bottles up time in a moment” and offers “a way to envision immortality” and “define power and permanence.” * Portraiture throughout history, then, provides a unique cultural record, revealing shifts in social dynamics and evolving attitudes regarding status and leadership.

For generations, African Americans experienced a kind of invisibility. Because they were disregarded by mainstream society, few records marking their lives exist prior to the end of the Civil War. Certificates of birth, marriage, and death are often difficult to find. Portraits and photographs of these individuals are even more rare. Following Emancipation, the documentation of African American culture improved. Better record-keeping practices and advancements in the field of photography allowed for a greater preservation of that community’s history and culture. Throughout the decades of “separate but equal” segregation and desegregation, trends in Black portraiture continued to evolve. Opportunities for self-representation increased, while new, more affordable technologies allowed for more frequent documentation of both celebratory occasions and moments of everyday life.

In more recent years, new generations of artists and photographers have put forth fresh narratives within the field of Black portraiture, showcasing both acknowledged leaders as well as overlooked members of the African American community. The result is a body of work that redefines old ideals regarding social value and establishes a more nuanced and comprehensive interpretation of “power and permanence.”

Early Portraiture

The origins of photography and portrait photography date back to the early 1800s. In 1826, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, a French inventor, presented the first surviving, permanent photograph, titled Point de vue du Gras (View from the Window at Le Gras), taken with a camera obscura. A little more than a decade later, in 1839, Louis Jacques Mandé Daguerre announced the invention of the daguerreotype. Almost immediately, this new process was used to produce the first known photographic portrait when Robert Cornelius took a picture of himself that same year, in doing so, creating the world’s first “selfie.”

As the process was refined over the next few decades, photography evolved from being a novel curiosity to a useful tool. The medical community was among the first to find uses for this new technology, but soon it was considered an essential aid within the fields of criminology and education, as well as the arts and sciences.

As photography developed, so did photographic portraiture. While painted portraits produced throughout history had been primarily used to memorialize the wealthiest and most powerful figures in society, photography enabled middle class citizens to commission affordable portraits of themselves or loved ones. By the late 1840s, daguerreotype portrait studios were prevalent throughout cities in Europe and the United States.

Mary Brice

Mary Brice, a member of Lynchburg’s enslaved community, lived and worked at Point of Honor during the 1850s. Very little is known about Brice, but she likely performed domestic services at that estate, serving as a cook, maid, and/or nurse.

Peter E. Gibbs was a respected daguerreian, actively working during the 1850s. Holding studios in Lynchburg, and later, Richmond, Virginia, Gibbs was admired by his peers, and described as an accomplished artist “without a superior anywhere.”

Singular in two respects, this daguerreotype is not only one of the earliest surviving photographs taken in Lynchburg, but it is also the only known identified portrait of an enslaved resident of the city taken before Emancipation. The original daguerreotype is housed in The Library of Congress.

Over the next few years, improvements in processing techniques, including the ambrotype and tintype formats, enhanced the clarity and detail of portrait photography. Less expensive than the daguerreotype, these advancements also reduced the time required for image exposure. Prior to this, photographers used props and braces to stabilize their subject, and encouraged a sitter to maintain a serious expression rather than a smile, which was more difficult to maintain for long periods of time.

The first two images above feature advertisements for photography studios in Lynchburg:

April 22, 1850, from Lynchburg Virginian newspaper. (Courtesy of Library of Virginia/Virginia Chronicle)

July 31, 1857, from Lynchburg Daily Virginian newspaper. (Courtesy of Library of Virginia/Virginia Chronicle)

Formats in Portraiture

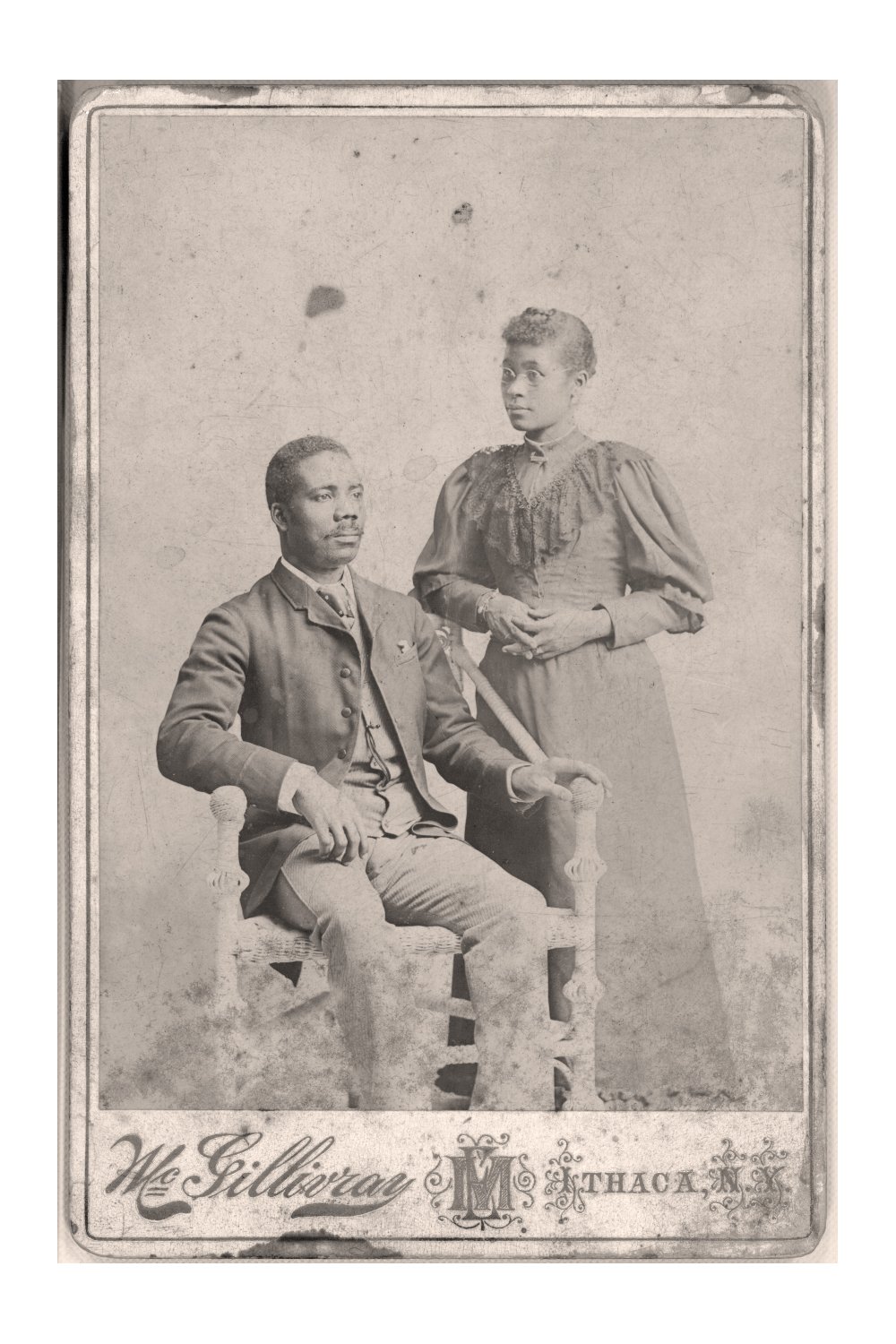

Beginning in the 1850s, it became popular to collect and share portraits thanks to new formatting techniques. The carte-de-visite (or “visiting card”) format was popularized by André-Adolphe-Eugène Disdéri of Paris in 1854. Similar to the size of a standard visiting card, the carte-de-visite consisted of a small photograph mounted on a card, which measured about 4 X 2.5 inches.

For social networking, publicity, or marketing reasons, people traded cards and often collected them in albums for home viewing. By the 1870s, millions of cartes-de-visite were being made throughout the world. Now regarded as an iteration of “social media,” these collections featured the portraits of not only acquaintances, friends, and family members, but also celebrities and politicians.

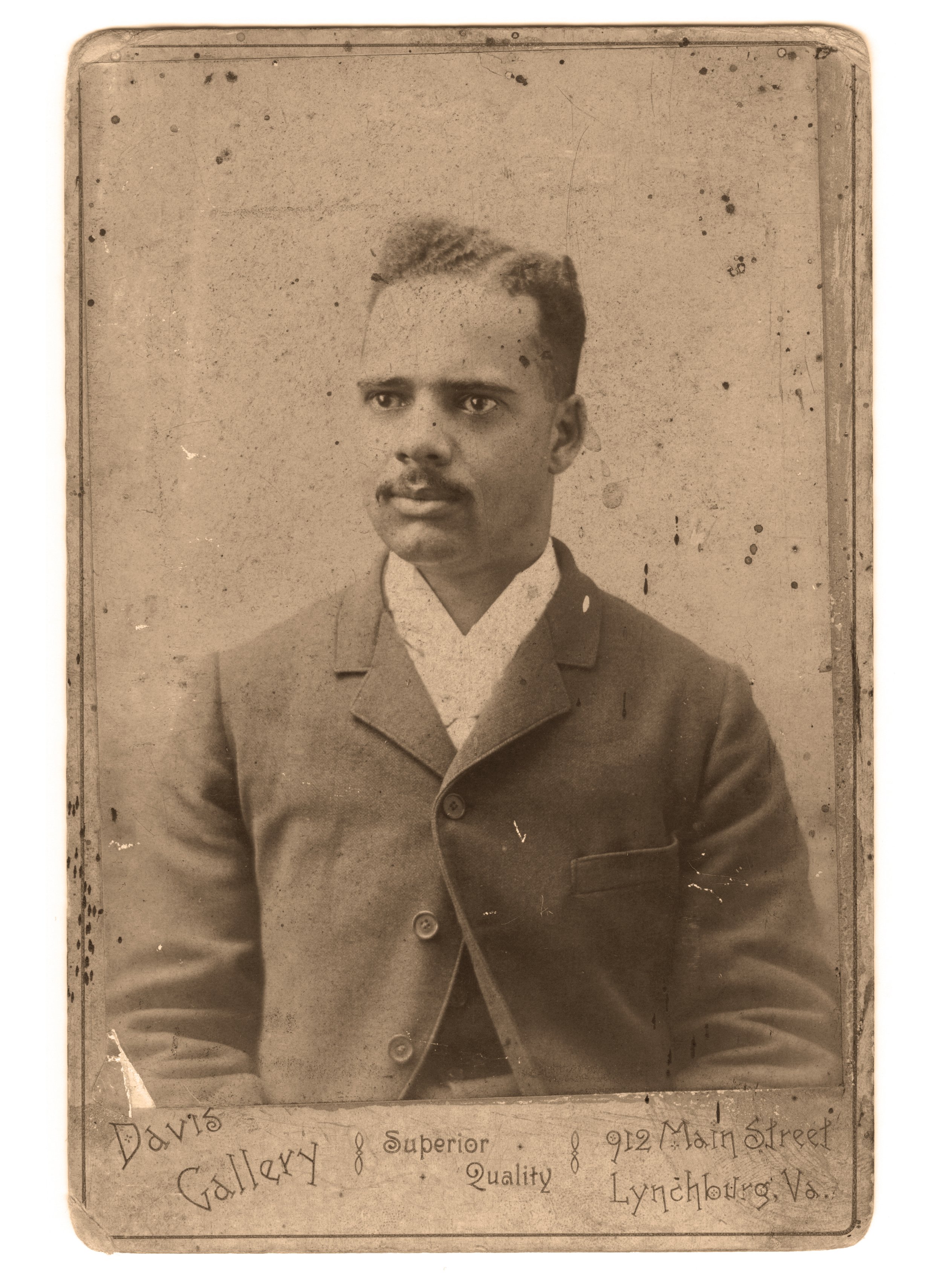

In 1866, the cabinet card photograph was introduced, and eventually surpassed cartes-de-visite in popularity. Cabinet cards were often studio portraits, produced with the photographer’s mark or imprint on the back. This new format was larger than the carte-de-visite, measuring about 6.5 x 4.25 inches.

Lynchburg hosted a number of daguerreans and photographers during the mid-to-late 1800s, including Peter E. Gibbs, Jesse H. Whitehurst, and A. H. Plecker. Many of these portrait studios advertised locally in newspapers such as The Lynchburg Virginian. In 1850, Whitehurst, who operated portrait studios in Lynchburg, Richmond, Petersburg, and Norfolk, between 1848 and 1853, reported “taking at the rate of twenty thousand likenesses annually.”

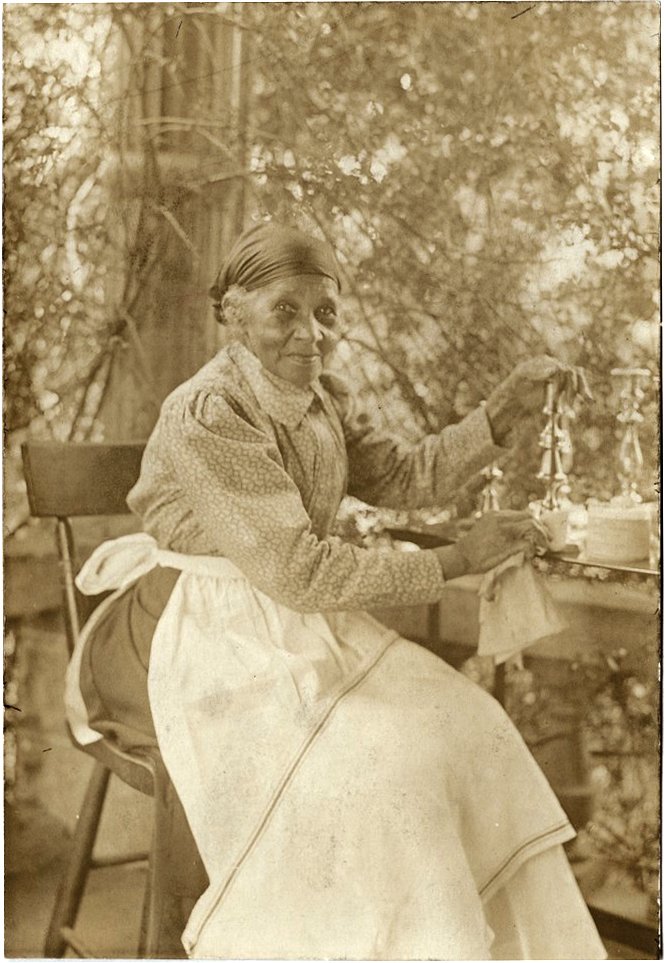

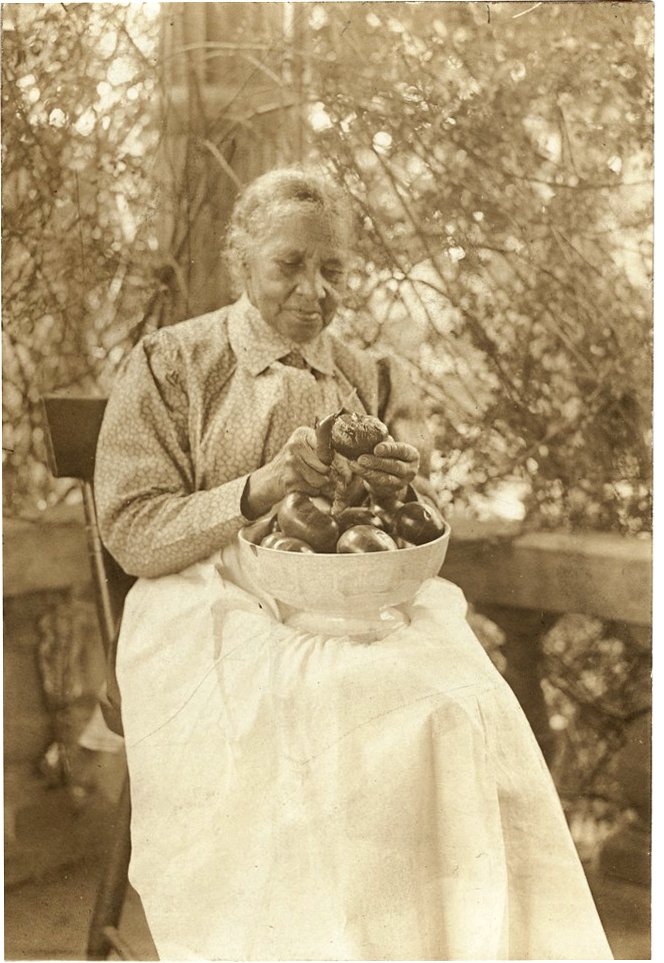

Martha Spence Edley

Likely produced between 1900 and 1910, the images of Martha Spence Edley are rare examples of identified portraits of a formerly enslaved resident of Lynchburg. The sepia-toned photographs are mounted on cardstock and unframed, and were taken on the porch of Edley’s employer’s residence on Rivermont Avenue. The photographer is unknown.

In these images, Edley is shown peeling tomatoes and polishing silver, activities that reflect her status as a “housemaid,” a role she performed for several generations of the same Lynchburg family as both an enslaved and free woman. The photographs were donated to the Lynchburg Museum in the 1930s, along with a bill of sale for “Martha,” dated 1849.

Martha Spence Edley was born enslaved in Powhatan County, Virginia, in 1826. At age 24, she was sold to prominent Lynchburg attorney, judge, and banker, David Edley Spence, who resided at 707 Church Street with his wife, Sarah. Martha Edley served as a personal maid to Sarah and nurse to the Spences’ infant daughter, Mary. Martha Spence Edley married George Edley, a man enslaved by a nearby plantation owner named David Rittenhouse Edley. They had three children, none of whom survived their parents. After George died in 1862, Martha never remarried.

During the Civil War, Martha Edley nursed sick and wounded soldiers at the Ladies Relief Hospital, an important hospital center located in the Union Hotel on Main Street. Following Emancipation, she remained in her position with the Spences, and ultimately served three generations of that family over the course of her life. Edley died in 1920 at age 94 and is buried in the Old City Cemetery with her husband and young children.

Betty Glover Garland ca. 1900

hand-colored photograph, octagonal convex frame

Gift of Carolyn Garland Brown

Rev. Sandy A. Garland, Sr. ca. 1900

hand-colored photograph, octagonal convex frame

Gift of Carolyn Garland Brown

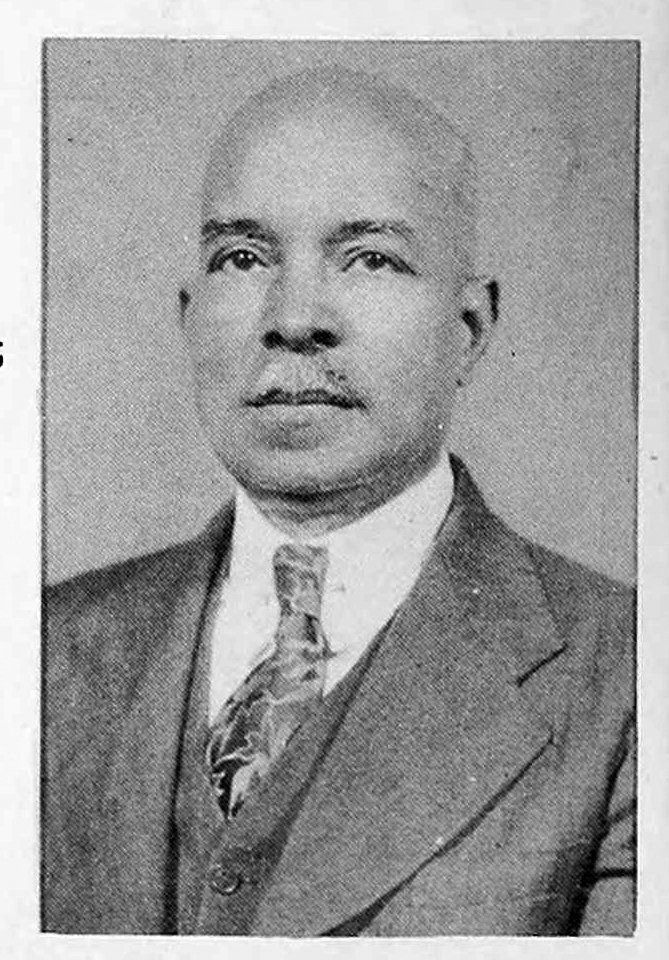

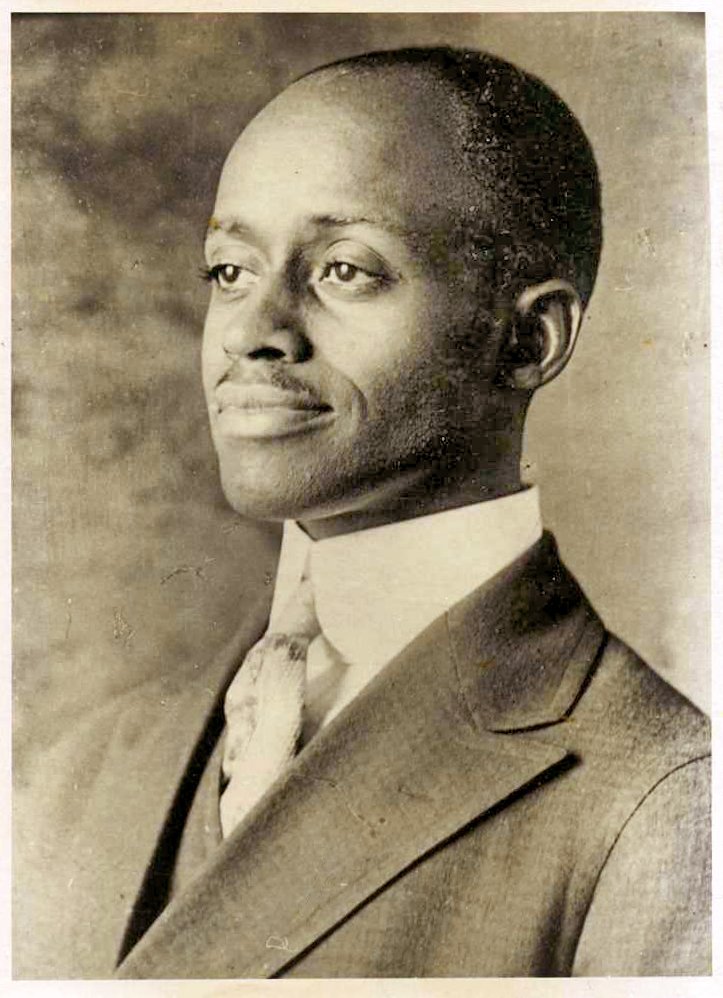

Respected Leaders: The Garlands

These photographic portraits, taken ca. 1900, depict Reverend Sandy A. Garland (1863 - 1930) and Betty Glover Garland (1872 - 1928) of Lynchburg, Virginia. Gifted to the museum by their granddaughter, Carolyn Garland Brown, they are displayed in the original octagonal frames, which were once fastened together by hinges. The photographs feature hand-coloring, a popular technique used between 1840 and 1940, also known as hand painting or overpainting. In this method, professional photographers manually applied color to enhance realism or artistry in a monotone photograph, using watercolors, oils, pastels, crayon, or other paints and dyes.

The Garlands were respected leaders within Lynchburg’s African American community during the late 1800s and early 1900s. They served several Baptist churches in the area, and through their ministry, formed deep connections within their congregation membership.

Sandy Garland was born in Nelson County, to parents, James and Irena Garland. In 1866, he and his family moved to Amherst County, and later, to Lynchburg, Virginia. Garland joined the Christian church in 1880 and was baptized by Rev. R. D. Merchant. Feeling called to the ministry, Garland began pursuing a license to preach. He earned a Doctor of Divinity Degree from Shaw University in Raleigh, North Carolina.

Rev. Garland served as pastor for several churches in the area, including Brookville

Baptist Church; New Morning Star Baptist Church, in Appomattox County, Virginia; and White Rock Chapel, White Rock Baptist Church, and Peaceful Baptist Church, in Lynchburg. An active leader within the community, Rev. Garland was connected with the Baptist Mission, the Star of the West Lodge, and the Virginia State Baptist Association. He also served as the Vice President of the Lynchburg Baptist Cemetery Association.

Betty Glover Garland, the daughter of Lucy and James Glover, a merchant, was born 1872, in Lynchburg, Virginia. She graduated from Lynchburg High School, and devoted herself to Christian service, later teaching at the Court Street Baptist Sabbath School. On July 15, 1891, she married Rev. Sandy Garland at Court Street Baptist Church. They had six children: Florence, Nannie, John, Sandy, Jr., Mildred, and Mary, who died as an infant. Betty Glover Garland died in 1928.

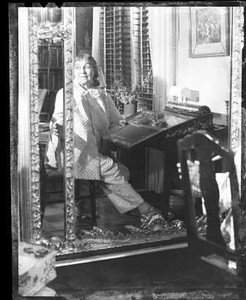

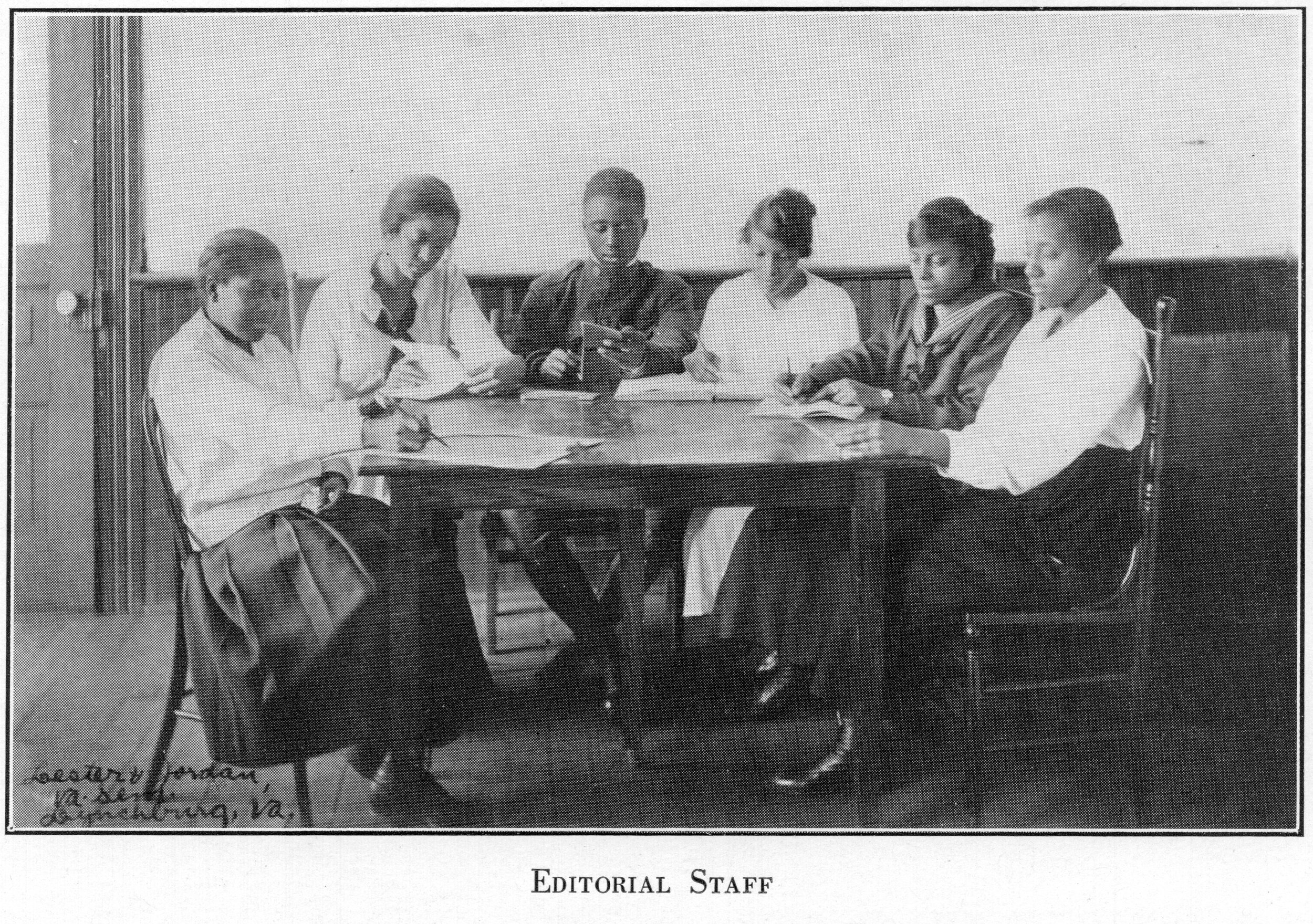

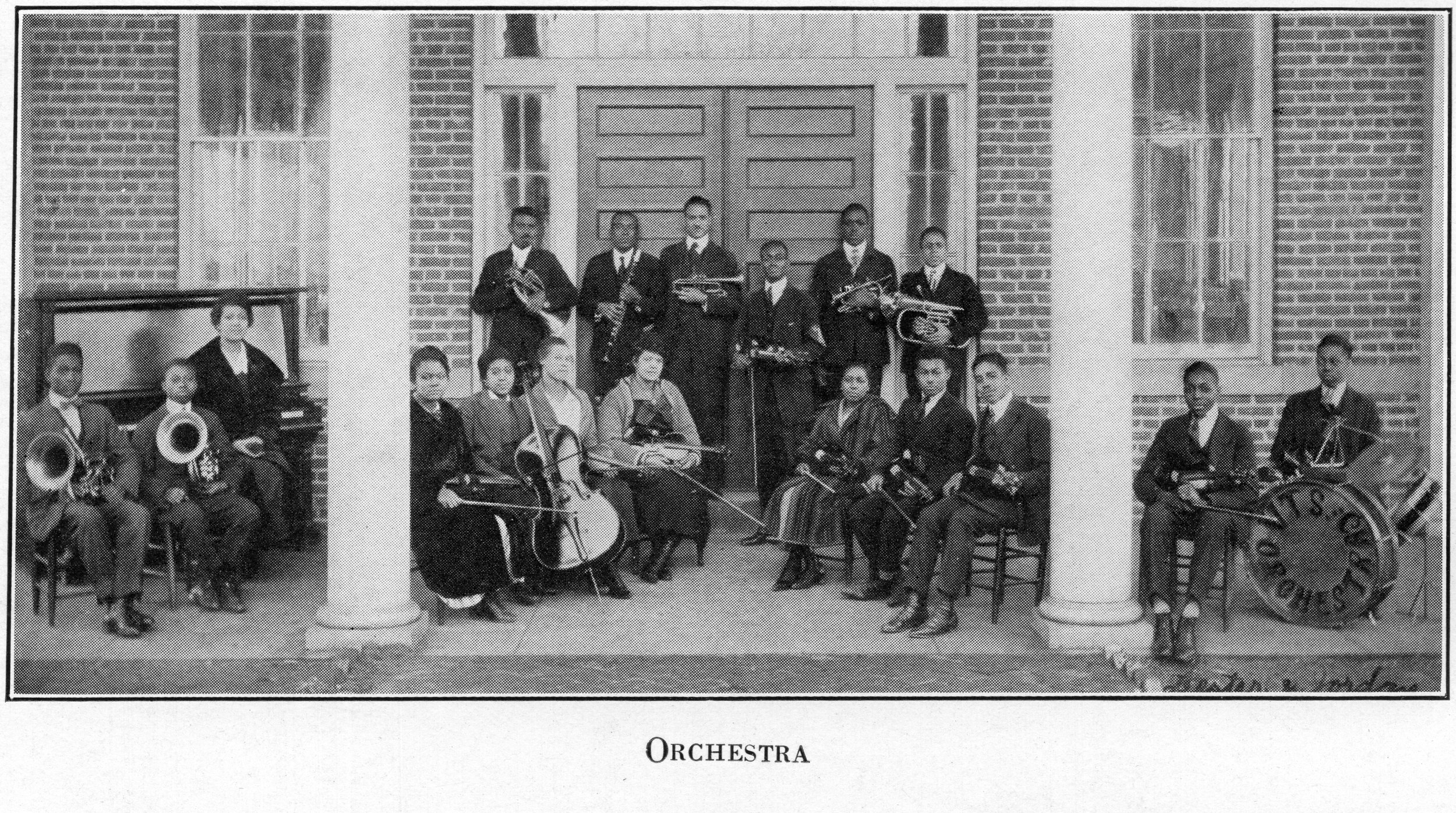

Black Photographers in Lynchburg: Lester & Jordan

Lynchburg was also the home of Lester & Jordan, a team of African American photographers active during the 1920s. Named for John Arthur Jordan (1887–1943) and Aurelius Pitts Lester (1885–1980), this studio was affiliated with the Virginia Theological Seminary & College in South Lynchburg. The graduate portraits and group photos created by Lester & Jordan feature students and faculty from the school, and offer a unique opportunity to understand what it means when African Americans are both behind and in front of the camera.

Lester, who graduated from Howard University, taught at Virginia Theological Seminary & College beginning in 1918, and resided in Lynchburg throughout the 1920s. Jordan also taught at VTSC through the early 1920s, before becoming an English teacher at Dunbar High School. According to the 1920–1921 Virginia Theological Seminary & College catalogue, both Lester and Jordan performed a number roles at the institution. Lester taught science, economics, Latin, education, and social science. He also played clarinet in the orchestra. Jordan was involved in the music program at VTSC, as well. In addition to playing violin, he conducted the band, orchestra, and chorus, while also instructing classes in French, Greek, Spanish, and English language and literature.

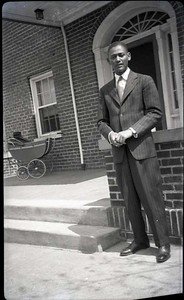

James T. Smith

Containing over 1,200 images, the Smith Photograph Collection chronicles African American life and culture in Lynchburg during the mid-20th century. Named for James Thomas Smith (1898–1986), the principal photographer behind this body of work, the collection captures rarely documented occasions in the lives of African American citizens during the 1940s, 50s, and 60s, the decades immediately preceding racial desegregation in Lynchburg. Many of Smith’s images depict celebratory events, including weddings and graduations, while others feature everyday moments of study, work, and contemplation. Taken during an era when African American achievements were excluded from mainstream news sources, these photographs preserve important people, places, and events, and provide a remarkable, collective portrait of the local Black community.

For thirty years, James Smith resided on the corner of Jackson and Fifth Streets in Downtown Lynchburg, with his wife, Lillian, a teacher at R. S. Payne Elementary School. Smith worked for the postal transportation service and considered photography, primarily, a hobby. Preferring to work with sepia-toned and black-and-white film, Smith constructed a darkroom in his Jackson Street home so that he could develop his own photographs. The negatives and prints that make up the collection were preserved and donated by Smith’s granddaughter, Pamela Smith-Johnson.

Smith produced a large number of portraits, some of which feature well-known leaders and exemplars within the community, including Anne Spencer and C. W. Seay. Many of the sitters in Smith’s work, however, have not been identified. The Lynchburg Museum welcomes your stories and your assistance as we continue to examine and explore the Smith Photograph Collection.

Black Photographers in Lynchburg: The 20th Century

With the introduction of affordable, easy-to-use cameras around the turn of the 20th century, the scope of photography expanded further. In 1888, George Eastman advertised his box camera, the Kodak No. 1, with the tagline “You press the button, we do the rest.” A few years later, in 1900, the Eastman Kodak Company released the Brownie camera, which retailed for one dollar. No longer solely relegated to professional studios, cameras were increasingly brought out into daily life and used to document a wider range of the human experience. As a result, portrait photography broadened to include more complex and dynamic imagery beyond the traditional picture of a posed sitter in a formal setting. A photographer might choose to capture the subject of a portrait at work or at play, in a living room or in nature. These choices were often in direct conversation with the personality and preoccupations of the sitter.

During this time, a number of important African American photographers emerged who were using this medium to illuminate overlooked corners of their culture. Artists such as James Van Der Zee (1886–1983), Gordon Parks (1912–2006), Roy DeCarava (1919–2009), and Carrie Mae Weems (born 1953) shaped perceptions of African American culture through their work by highlighting the once-hidden nuances within their respective environments. In Lynchburg, photographer James T. Smith created a similarly ground-breaking body of work. Working in the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, Smith produced hundreds of photographs that documented well-known leaders as well as everyday figures within the city’s African American community.

Photographer, James Thomas Smith, ca. 1967

Courtesy of Pamela Smith-Johnson and News & Advance (published June 16, 2017)

Black Portraiture in Painting: Artist & Subject

Jon Roark 2018

Mary Brice at Point of Honor

egg tempera on clapboard

Jon Roark

Lynchburg resident, Jon Roark, is an award-winning artist and educator, who specializes in illustration and painting. He works in a variety of media, including watercolor, acrylic, and egg tempera, an ancient method of painting in which pigments are mixed in a water-soluble binder of egg yolk. Roark studied European History and Studio Art at Lynchburg College (University of Lynchburg), and graduated from the Fashion Institute of Technology, New York, with a degree in Illustration. After serving as an art director for several years, he devoted himself to instruction, both at University of Lynchburg and Heritage High School, where he taught art for fifteen years.

In 2018, Roark and his students produced a collection of art work that examined the history of Lynchburg’s African American community through portraiture. Initially created as a response to the violent 2017 rally in Charlottesville, the project offered Roark an opportunity to foster empathy in his students while teaching important artistic techniques. The collection, consisting of about eighty portraits, was featured at Lynchburg’s Academy Center for the Arts, as well as the Legacy Museum of African American History. After the success of these shows, the Academy commissioned a second show for the following year on the theme of Juneteenth.

This project with his students inspired Roark to explore the history of Lynchburg’s African American community further through his own artwork. In both Mary Brice at Point of Honor (left) and Emancipation Gothic (below), the artist produced portraits of enslaved individuals who had lived in Lynchburg, hoping that he might “give them a voice through art.” Roark chose to use the egg tempera medium because “it has a glowing quality to its surface and richness I thought these African American subjects deserve.” Recently, Roark expressed: “My hope as an artist is that the faces I bring forward in these portraits are treated in memory with the kindness and respect they deserve. If I have been able to lift them up, and give them a voice, they, too, have been invited for a second show.”

Symbolic elements in Emancipation Gothic:

Jon Roark embedded a number of symbols and references into Emancipation Gothic, many of which are Lynchburg specific and speak to the city’s history of slavery.

The title and basic design of the painting allude to Grant Wood’s Regionalist painting, American Gothic.

In this work, two members of Lynchburg’s enslaved community are memorialized: Richard Toler and Martha Spence Edley, both of whom weathered the transition from slavery to Emancipation.

The house in the background is based on the oldest surviving house in Lynchburg, the Miller-Claytor House, which was built in the 1790s and later preserved in Riverside Park.

The sign marked “Indian Queen Tavern,” refers to an establishment once located in downtown Lynchburg, where enslaved individuals were auctioned and sold.

The red banner, located on the right along the roofline of the house, refers to a specific practice within the slave trade. At auction houses, slave traders displayed a red banner to announce sales. Traders pinned scraps of paper to the banner, which communicated details of specific individuals coming up for sale.

In the foreground, the cast iron fence acknowledges Lynchburg’s shift to manufacturing after the Civil War.

In the far, lower right corner, a rusty shackle and chain hanging on the fence represent the complicated transition to freedom after Emancipation. While the shackles hang open, their presence is a reminder of the freedom-limiting restrictions placed on African Americans during that time.

For Roark, flowers growing through the fence are meant to represent “the beauty created by our formerly enslaved citizens despite the obstructions thrown up by society.”

The red flowers are nasturtiums, a variety that poet Anne Spencer loved and grew in her garden.

Finally, the crow is a direct reference to the Jim Crow laws, the state and local laws which enforced racial segregation throughout the American South for decades after the Civil War. For Roark, the crow, which seems “content among the flowers” is a “reminder of the hate that we still fight against every day.”

Jon Roark

Emancipation Gothic 2023

acrylic and oil on canvas

Christina Davis

Portrait of Murrell Warren ("Teedy") Thornhill, Jr. 2023

acrylic and oil on canvas

Lynchburg’s Christina Davis

Christina Davis is a self-taught fine artist and painting instructor at Academy Center of the Arts, where she teaches classes in acrylics and gouache. A native and resident of Lynchburg, Davis specializes in large-scale outdoor murals, which can be viewed in various locations throughout the city. Her work can also be found inside several buildings in Lynchburg, including the R. S. Payne Middle School and the YMCA of Lynchburg. Writing in October, 2023, Davis expressed that, "artists who create black portraiture are able to give voice to the feelings and experiences of their viewers, while also exploring their own personal narratives. Through their work, they are able to capture the essence of their subjects and convey their stories in a way that can be appreciated by all.”

Created in an abstract style that features bright, vivid colors, this portrait was painted for the Lynchburg Peacemakers Silent Auction held on July 29, 2023 at Point of Honor, and commemorates Murrel Warren ("Teedy") Thornhill, Jr. (1921-2016), Lynchburg's first African-American mayor.

Mayor Thornhill graduated from Lynchburg’s Dunbar High School in 1940, and later attended and graduated from St. Emma Military Academy, near Powhatan, Virginia. A funeral director by profession, he served as the president and owner of Community Funeral Home on Fifth Street, and held a membership at Court Street Baptist Church, where he was also a trustee.Thornhill was involved in politics throughout his life. For over 40 years, he presided over the Lynchburg Voter’s League and won the Ward II seat on Lynchburg City Council in 1972. In 1990, he became Lynchburg’s first African American Mayor. Due to failing health, he retired two years later in 1992.

Ann van de Graaf & Delores “Dee” Fowler

Lynchburg artist, Ann van de Graaf, was born in Africa, and spent her early years living in East Africa and England. She studied drawing and painting with the Lynchburg Art Club and Lynchburg Fine Arts Center, and graduated from Randolph Macon Woman’s College in 1974, with a double major in Art and Sociology. From the beginning of her career as an artist, Ms. van de Graaf has explored themes related to racial equality and created work that champions figures from Lynchburg’s African American community. One of her most respected works, Lord, Plant My Feet on Higher Ground (1993), is a large-scale, panoramic triptych, depicting individuals associated with the civil rights movement in Lynchburg during the 1960s and 1970s. That work is on permanent display at the Legacy Museum of African American History in Lynchburg.

On the Dais is inspired by a civil rights event (ca. 1970) at Court Street Baptist Church, where Delores “Dee” Fowler, along with other leaders from the Voters League and NAACP, assembled to address concerns regarding the improvement and redevelopment of Lynchburg for the African American community at that time. In attendance when the participants processed in, the artist observed that every participant was male except Fowler. According to van de Graaf, Ms. Fowler “never pushed for recognition,” but also wasn’t afraid to draw attention. Aware that she would be the only woman on the dais surrounded by men, Fowler chose to wear the regal color purple so that she might stand out. For van de Graaf, the color perfectly expressed Fowler’s elegance and subtle power.

Ann van de Graaf 1984

On the Dais (Deloris “Dee” Fowler)

oil on canvas

Ann van de Graaf 1985

Reflections (L. Garnell Stamps)

watercolor, ink

Ann van de Graaf & L. Garnell Stamps

Lynchburg native, L. Garnell Stamps (1934 - 2014), was a teacher, poet, and respected leader within the city’s civil rights movement. Stamps graduated from Dunbar High School, earned a B.A. in English from University of Maryland, Eastern Shore, and took graduate classes at University of Lynchburg and University of Virginia. He later taught English in the Lynchburg School System. For several years, Stamps also hosted a televised talk show,“The Real Viewpoint,” on which he interviewed a number of notable figures, including Ms. Rosa Parks, Dr. Maya Angelou, Anne Spencer, Gwendolyn Brooks, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

As an orator and writer, Garnell Stamps is remembered as someone who understood the power of words. In 1982, Stamps, along with Ann van de Graaf and Barry Donald Jones, created Bargara Press, a publication committed to representing female and minority voices. In 1983, Bargara published “This Robe of Flesh, An Elegy Written after the Death of the Dreamer, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.,” a collaboration written by Stamps and illustrated by van de Graaf. “Praise Song for an Alma Mater,” published in 1989, featured a commemorative ode, written by Stamps, in honor of Dunbar High School.

Share Your Story

Do you have any local African American portraits or information related to a portrait? We would love to hear from you! The Lynchburg Museum System is actively seeking material to illustrate the full history of our city.

Call (434) 455-6226 or email museum@lynchburgva.gov