Exhibit Curated and Digitized by Laura Crowe

Introduction: Early Barbers in Lynchburg

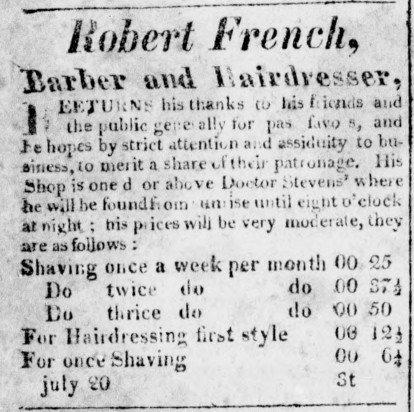

In the 19th century, barbers were an important part of everyday life in Lynchburg. It was common practice for men to enlist the services of a barber for a shave multiple times a week or even daily. Those who did not may still have visited a barber several times a month for a haircut or other personal grooming services. Early Lynchburg barber Robert French advertised that his patrons could choose a subscription-style payment in order to save money per shave.

Free Black Barbers

Lynchburg’s most notable antebellum barbers were free Black men who primarily barbered for a white clientele. These barbers were businessmen and entrepreneurs who established themselves within the challenging socio-political climate of the antebellum South and became prominent figures in the city. Three well-known barbers were Armistead Pride, Leander Harrison, and Claiborne Gladman. This trio moved within the same circles and were all part of the small group of “free Black elite” that existed in Lynchburg prior to 1865.

Advertisement, Lynchburg Press, 1821

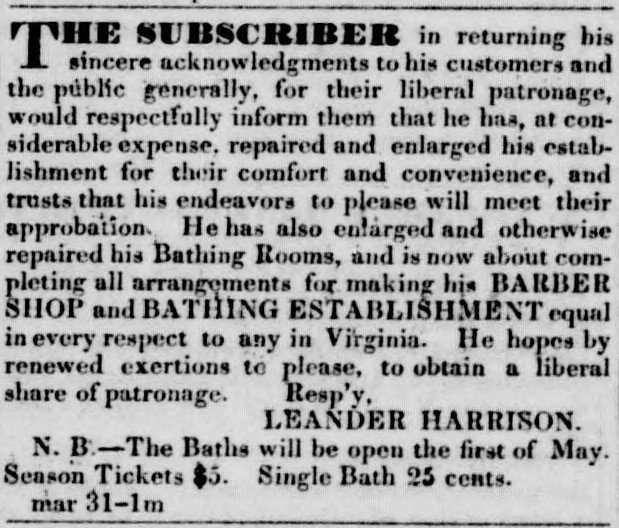

Advertisement from the Lynchburg Republican, 15 October 1855

Leander “Lee” Harrison (1826–1903)

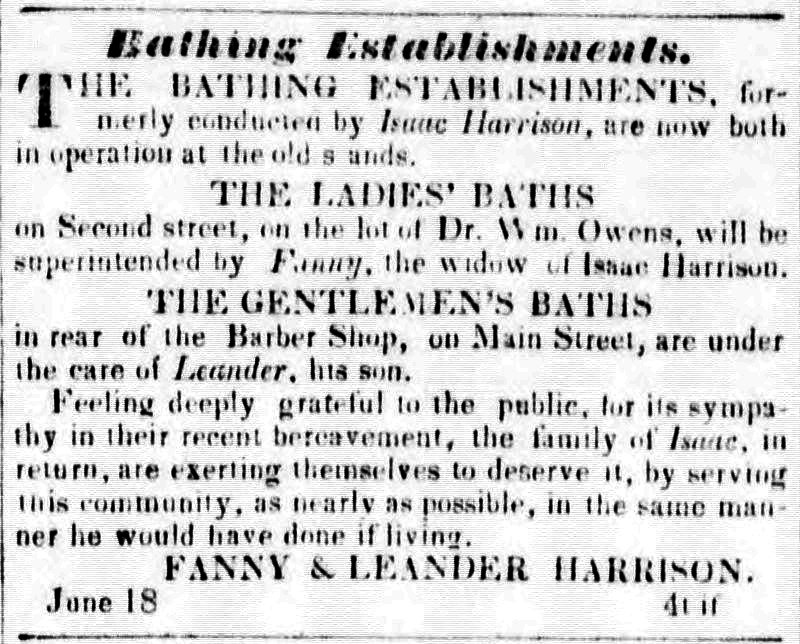

Leander Harrison was born into slavery in Lynchburg in 1826. His father, Isaac Harrison, a well-established barber, was emancipated when Leander was a boy and set up a business in Lynchburg. Leander and his mother Fanny remained enslaved, but from his father, Leander learned the trade of barbering. It was through his efforts as a barber that Leander Harrison was able to earn and save the money to purchase his own freedom for $900 at the age of 24. Shortly after, he married a woman named Martha A. Rogers who was enslaved in Richmond. In order to be with his family, Leander Harrison was forced to “rent” his wife and their children from the man who enslaved them so that they could live with him in Lynchburg.

Noted writer George W. Bagby mentioned Leander Harrison by name in one of his sketches and described Harrison as “the best barber in the State, according to my thinking.” Leander Harrison’s son Charles was also a barber in Lynchburg for a number of years. He first worked at his father’s barber shop, and later at the Hotel Carroll barber shop. He ultimately gave up barbering to become a minister in the Episcopal Church and moved to Charleston, South Carolina.

Below:

Leander Harrison Advertisement, Lynchburg Virginian, 31 March 1851

Fanny and Leander Harrison notice, Lynchburg Virginian, 18 June 1846

Armistead Pride (1787–1858)

Armistead Pride was one of Lynchburg’s preeminent barbers and operated in the city for around 50 years. In addition to traditional barbering, Armistead Pride created his own hair tonic, which he regularly advertised in the Lynchburg Virginian, Lynchburg Daily Virginian, and the Lynchburg Republican.

Pride family barber shops remained a fixture in Lynchburg for many years even after Armistead Pride’s death. His son, William Royall Pride (1820–1891), and grandsons Armistead Pride and Claiborne Gladman Pride Sr. all followed in the family trade. In Armistead Pride’s will he specified that all of the furniture and barbering implements from his shop were to be inherited by his son William Royall Pride upon his death. William Royall Pride was married to Lucinda Gladman, daughter of the barber Clairborne Gladman (1788–1855).

Notice from the Lynchburg Virginian, 1850

Portrait of Leander “Lee” Harrison, circa 1890

Courtesy of Old City Cemetery/Southern Memorial Association

Leander Harrison Notice, Lynchburg Virginian, 7 May 1846

Artifacts: Tools of the Trade

Descriptions of objects above from right to left:

Barber’s Trimming Shears, early 20th century

These barber shears were owned by barber Claiborne Gladman Pride Sr. (1857–1933), the son of William Royall Pride and Lucinda Gladman Pride. Claiborne Gladman Pride Sr. was named for his maternal grandfather, Claiborne Gladman, who was a well known barber in Lynchburg, and his paternal grandfather was barber Armistead Pride. Claiborne Pride Sr. followed in his family’s footsteps and also became a barber. He operated his barber shop on the 200th block of 10th street for more than 40 years.

Gift of J. Claiborne Walton & Family 2023.35.1

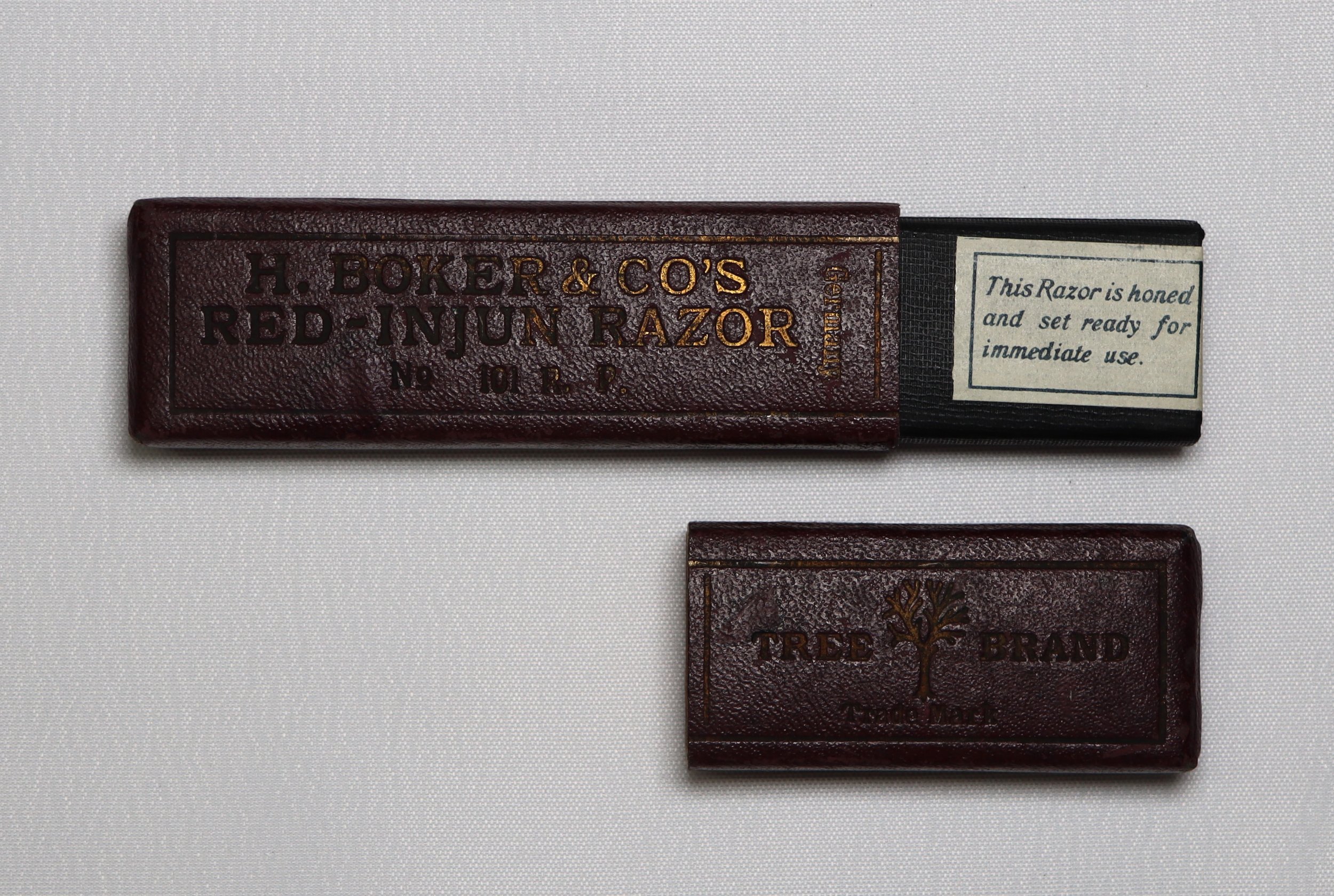

Straight Blade Razor and Leather Case, circa 1930

Before the invention of safety razors or electric razors, the straight razor was the principal tool used for shaving the face. From the time they were first widely manufactured in the early 18th century until well into the 20th century, straight razors could be found in barber shops around the world. Shaving with a straight razor required skill and precision and could take years for a skilled barber to perfect.

This razor and case came from Bill's Barber Shop, which first opened in Lynchburg in the early 1940s and was located at 107 9th Street between Main and Commerce for more than 20 years. The razor is a “Silver King” model made by Wilbert Cutler of Chicago, and the embossed leather case was made by the German company H. Boker & Co.

Gift of Eloise Reams 2003.31.2 a and b

Kizure Hot Curling Irons, 1980s

Marcel irons first became popular in the early 20th century to achieve the fashionable hairstyles of the period. They continue to be used by professional hair stylists today.

Loan Courtesy of Christy Hughes of Diamond Cutz by Christy

Hot Comb, 1950s

The hot comb was invented in the late 19th century. It is heated and used to press and straighten the hair.

Loan Courtesy of Christy Hughes of Diamond Cutz by Christy

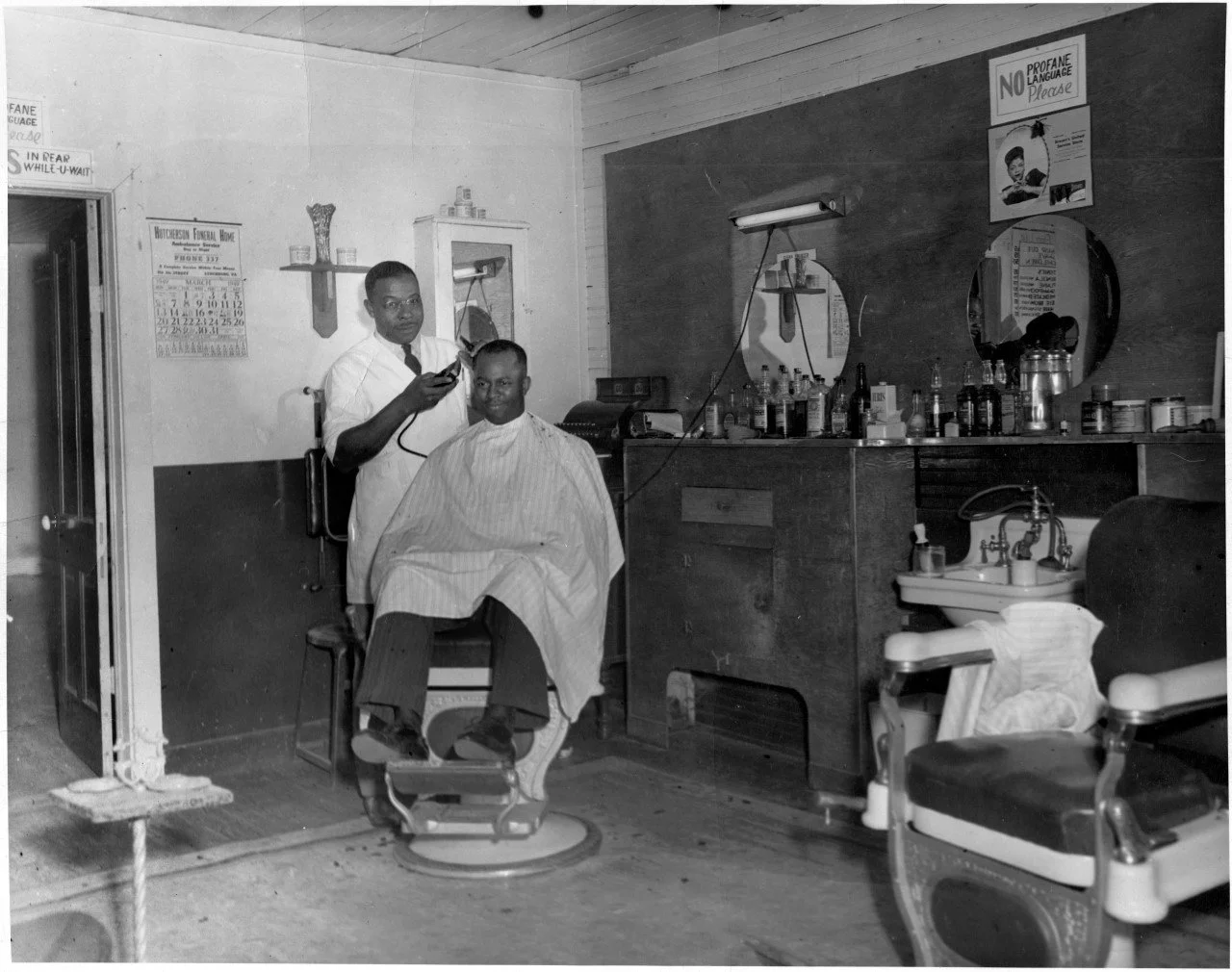

Glenn Younger’s Barber Shop, 903 1/2 Fifth Street, March 1949

Glenn D. Younger (1903–1994) was a long-time barber on Fifth Street in Lynchburg. Younger spent the 1930s and 40s working as a barber at the Hutcherson Barber Shop and later at Merriman’s Barber Shop before opening his own establishment around 1949. Younger was active in the community and served as president of the Court Street Baptist Church Men’s Chorus.

Courtesy of Court Street Baptist Church

Advertisement for Frances Southall’s Beauty Shop, Lynchburg City Directory, 1937.

The Business of Beauty

Beauty shops and parlors sprang into being around the turn of the 20th century. Prior to this, women’s beauty care and hairdressing had largely taken place within the private sphere of the home. One reason for this trend was the changing fashions for women’s hair along with the increasingly mainstream use of cosmetics. Women were also entering the workforce in greater numbers and were making new places for themselves in society and the professional world. Nationally, businesswomen like Martha Matilda Hopper, Madam C. J. Walker, and Helena Rubinstein were at the forefront of the burgeoning industry of women’s beauty. It proved to be an immensely profitable field of commerce and Lynchburg, like the rest of the country, soon had an abundance of businesses centered around women's beauty, many of them owned or operated by women.

Handbill for Rose Marie Beauty Shop, circa 1927

Rose Marie Beauty Shop opened in 1927 at 715 Church Street and was one of only three businesses identified as “beauty shops” in the Lynchburg City Directory that year. Within a decade that number had grown to 39.

Gift of Mr. S. Wayne Staples 93.5.24

Cutting Edge: Lynchburg’s First Beauty Parlors

The advent of beauty parlors in Lynchburg coincided with the introduction of “bobbed” hair. By the mid-1910s, young women were increasingly experimenting with shorter hairstyles as a way to eschew traditional ideas of femininity and rebel against social norms. By 1920, the bob and other short coiffures had become highly fashionable, and new hairstyling practices and techniques were rapidly adopted by hairdressers to meet the demand. Marcel curls, permanent waves, and finger curls all became standard offerings at beauty salons. Sheard’s Beauty Parlor was no different, and Florence Sheard advertised such services by 1920.

New hairstyle trends in the 1950s and 60s boosted the business of another Lynchburg beauty salon owner several decades later. After opening in 1953, Ralph’s Salon gained a reputation for its stylish bouffants and, later, beehives. At Ralph’s School of Cosmetology (later Ralph’s Beauty College), which opened in 1961, students learned to create these popular looks for their clients.

Sun Dial, 6 November 1920

Amherst New Era-Progress, 25 April 1963

The Frances Southall Beauty Shoppe

Lynchburg native Frances Dowdy Southall Stump (1908–1964) first delved into the world of beauty while working as a stenographer for the Craddock-Terry Shoe Company’s West End Factory. She used her vacation time to take a course on marcelling and finger waving hair, and then spent her weekends working at a beauty shop. She practiced her skills by offering free fingerwaves to the female factory workers at Craddock-Terry.

Southall first operated her beauty business out of her home, but was able to open the Frances Southall Beauty Shoppe at 216 Eleventh Street in 1932. By 1936 she had around a dozen employees and was featured in an article in the Lynchburg sesquicentennial newspaper. The summer before that article was published, Southall took a road trip to Hollywood where she visited the hairdressing and makeup departments at Paramount, Fox, and Universal in order to bring the latest fashions back to Lynchburg.

Frances Dowdy Southall married her second husband, Arthur E. Stump Jr., an insurance agent and lieutenant colonel in the US Air Force in 1937. By 1940 she had transitioned to operating her beauty shop out of her home on Rivermont Avenue. There was a break in her operations in the following years, but by 1948 she was once again running a beauty business out of her home, with the new name of “Mrs. Frances S. Stump’s Beauty Shoppe.” In her later years she worked as the assistant manager and bookkeeper of the Randolph-Macon Woman’s College bookstore.

Frances Southall

Pictured in the Lynchburg News, 1936

Advertisement for the Frances Southall Beauty Shoppe, Nelson County Times, 1937

Advertisement for the Frances Southall Beauty Shoppe, Nelson County Times, 1934

Selma's Beauty and Flower Shop, 1962. The shop on the left is Overstreet's Bakery and on the right is the Portsmouth Fish Company. The car in the image is a 1957 or 1958 Studebaker Hawk.

Lynchburg Museum System, 74.489.37

Selma’s Beauty and Flower Shop

Selma’s Beauty Shop first opened in 1934 at 901 ½ Fifth Street and moved to 1002 5th Street in 1937. Selma’s Beauty and Flower shop operated out of 612 Fifth Street from 1959 onwards, as seen in the photo on the left. The beauty shop remained in operation until 1972. Selma’s was notably included in the Virginia Green Book from 1938 to 1958 as a safe location for Black travelers to stop. It was one of around a dozen Lynchburg businesses and homes listed during the Green Book’s years of publication.

Selma’s long-time proprietor was a woman named Selma R. Simms. However, for the shop’s first several years of business, both Selma R. Simms and another woman named Mildred Francis are alternately listed as running the beauty shop. It is likely that they worked together to first open the beauty shop. Selma Simms moved to Lynchburg in the early 1930s and worked in the beauty industry in the city for more than 30 years before moving out of state in her retirement.

Mayfair Beauty College

Lexington Gazette, 1939

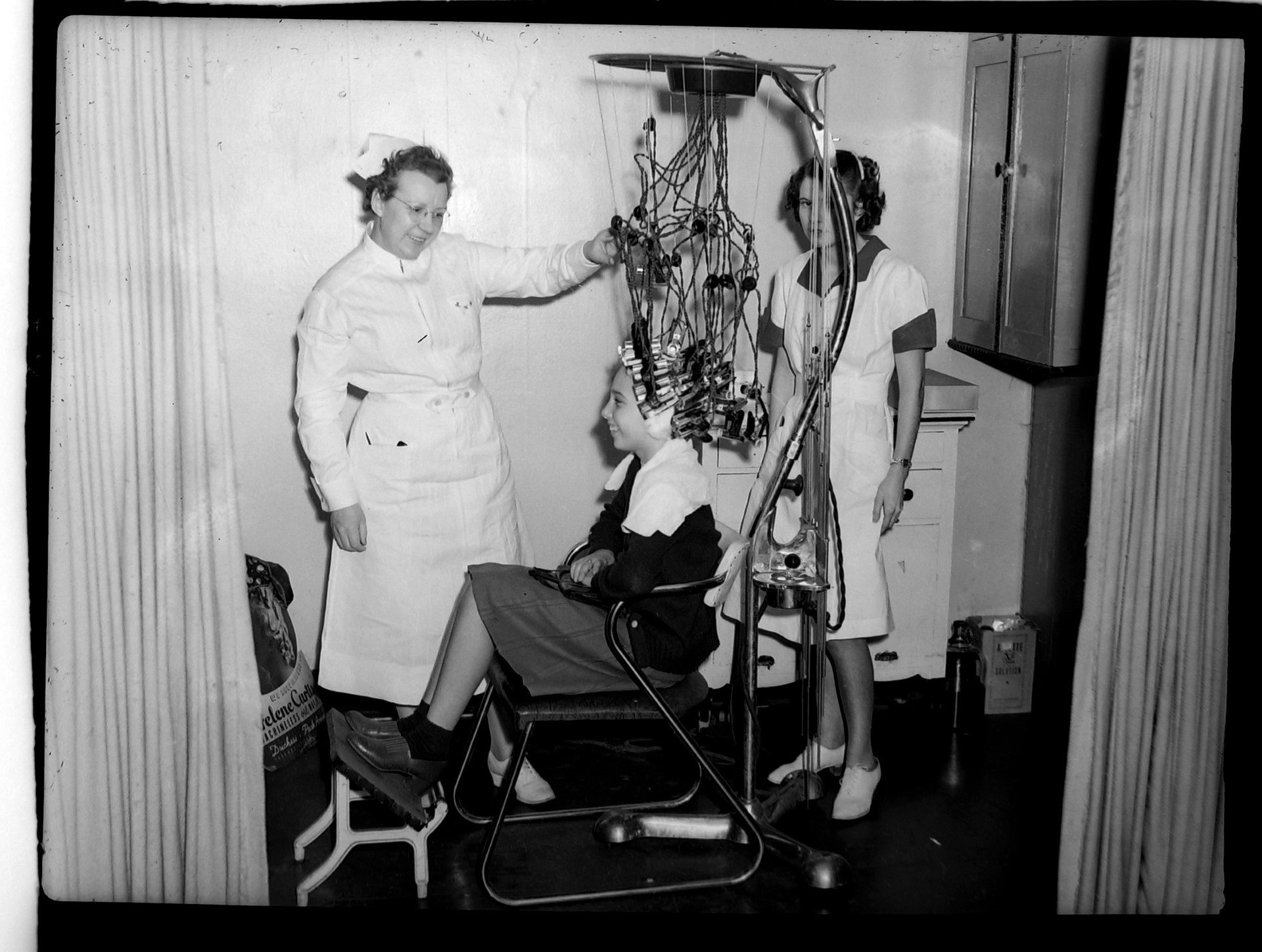

As more and more women entered careers in women’s beauty, beauty colleges opened around the country in order to fill the ranks of beauticians and hairdressers. Mayfair Beauty College opened in Lynchburg in the 1930s and was a prominent beauty college in the region, which operated for more than 30 years and primarily instructed young white women.

Photographs of Mayfair Beauty College, 1940

Courtesy of Nancy Blackwell Marion

Stokes’ Institute of Cosmetology

The owner and director of Stokes’ Institute of Cosmetology was Virginia Lewis Stokes Brown (1910–2000). She first opened Stokes Beauty Salon in the late 1940’s with her husband Leon B. Stokes (1905–1959), then later opened Stokes’ Institute of Cosmetology in 1950, both at the same address on Twelfth Street. Stokes’ Institute provided professional degrees in cosmetology to many African American women in Lynchburg and the surrounding area. The school’s student base included a number of graduates of Dunbar High School.

Stokes’ Institute of Cosmetology, as well as its associated salon Stokes’ House of Beauty, remained open until 1975.

Advertisement for Stokes’ Institute

Amherst New Era-Progress, 1953