Exhibit Curated and Digitized by Austin Gaebe

Introduction

Fighting a war requires an immense amount of bureaucratic organization, and the Civil War (1861- 1865) was no different. In the midst of a nation at war, Central Virginians recorded their experiences through the form of legal documents, personal correspondences and even receipts. Today, historians can glean relevant and surprising information about life during the Civil War through these documents. In this exhibit, you will see examples of archival material from the Lynchburg Museum System’s collection in order to help visitors better understand what daily life during wartime was like.

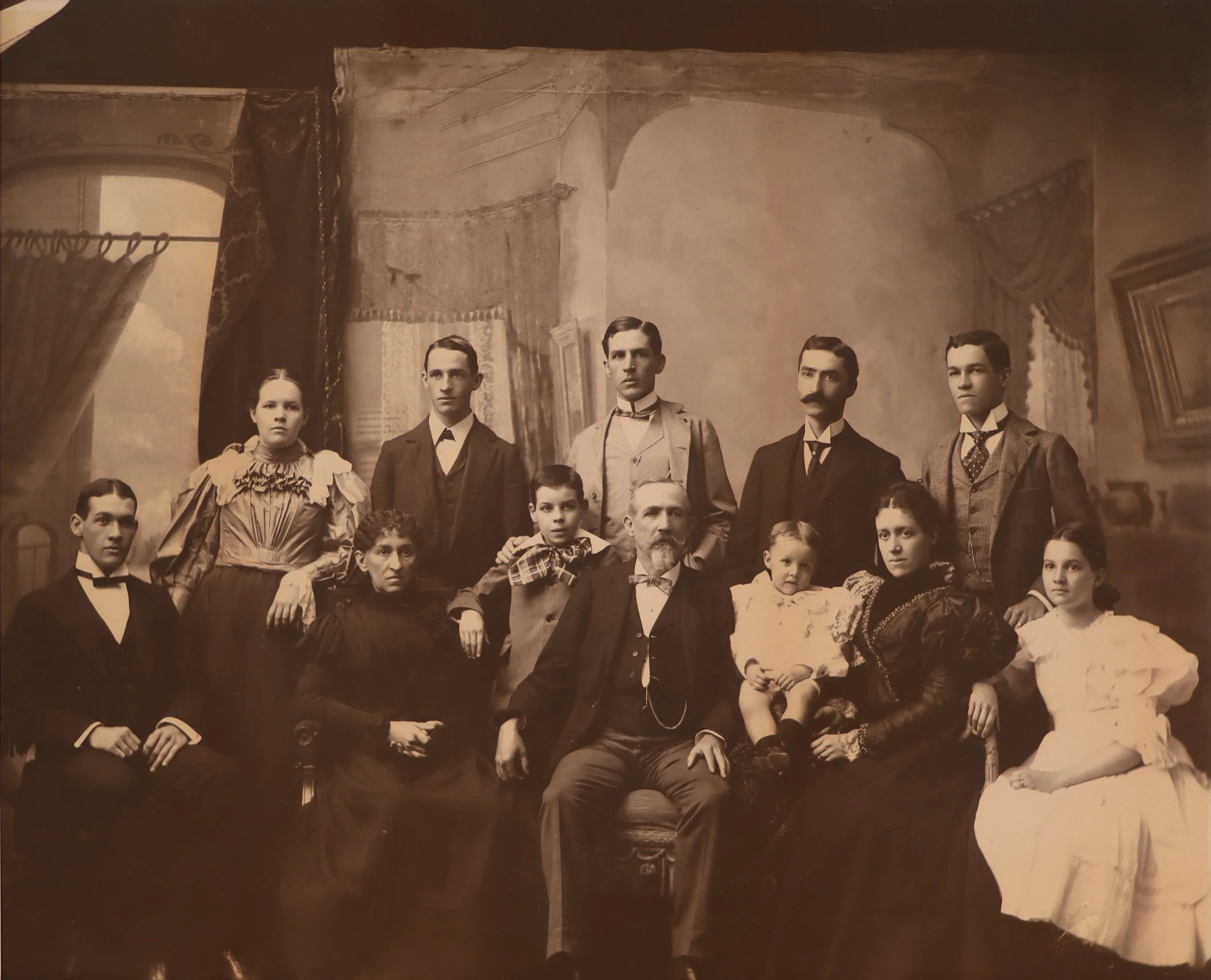

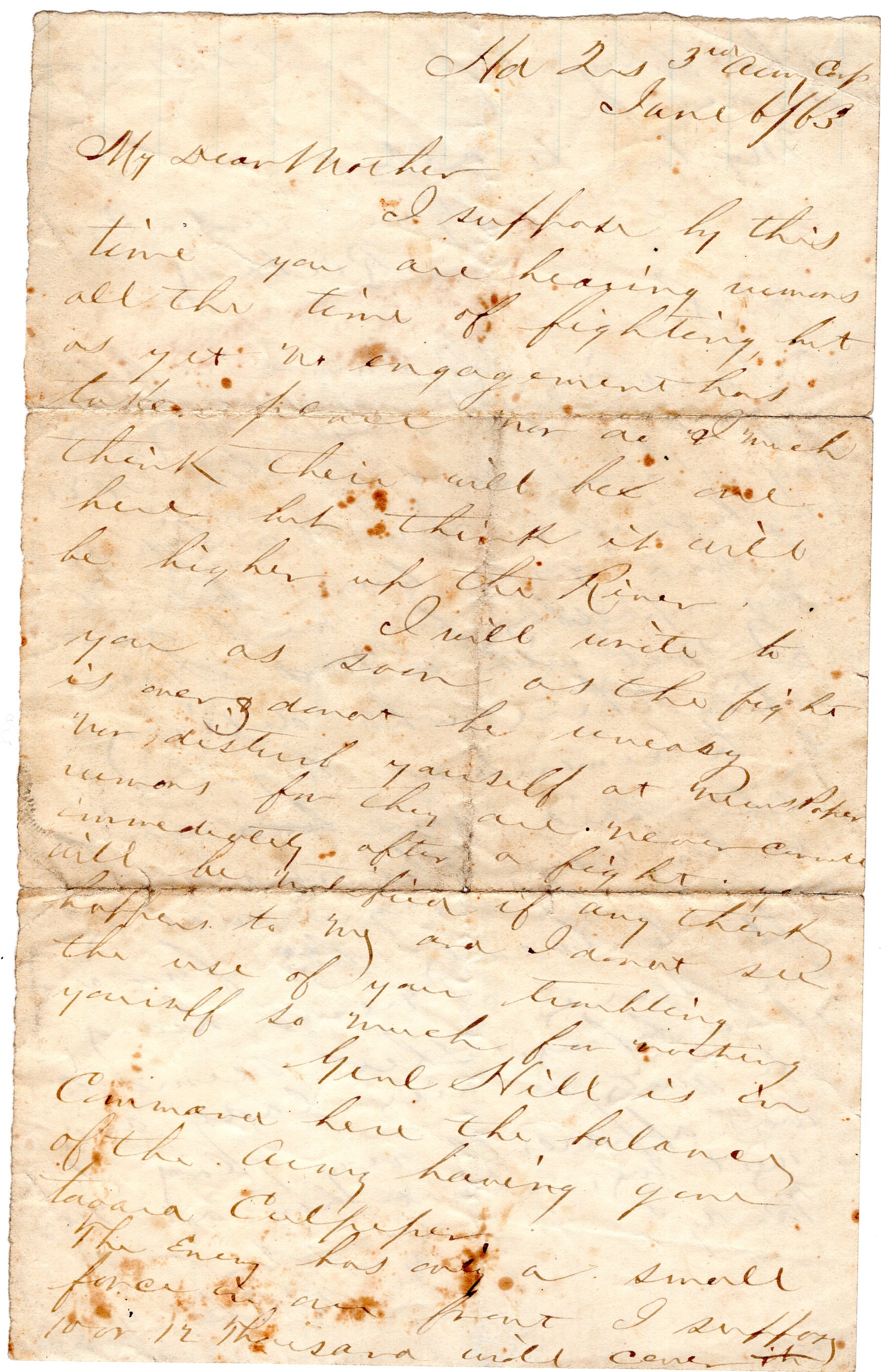

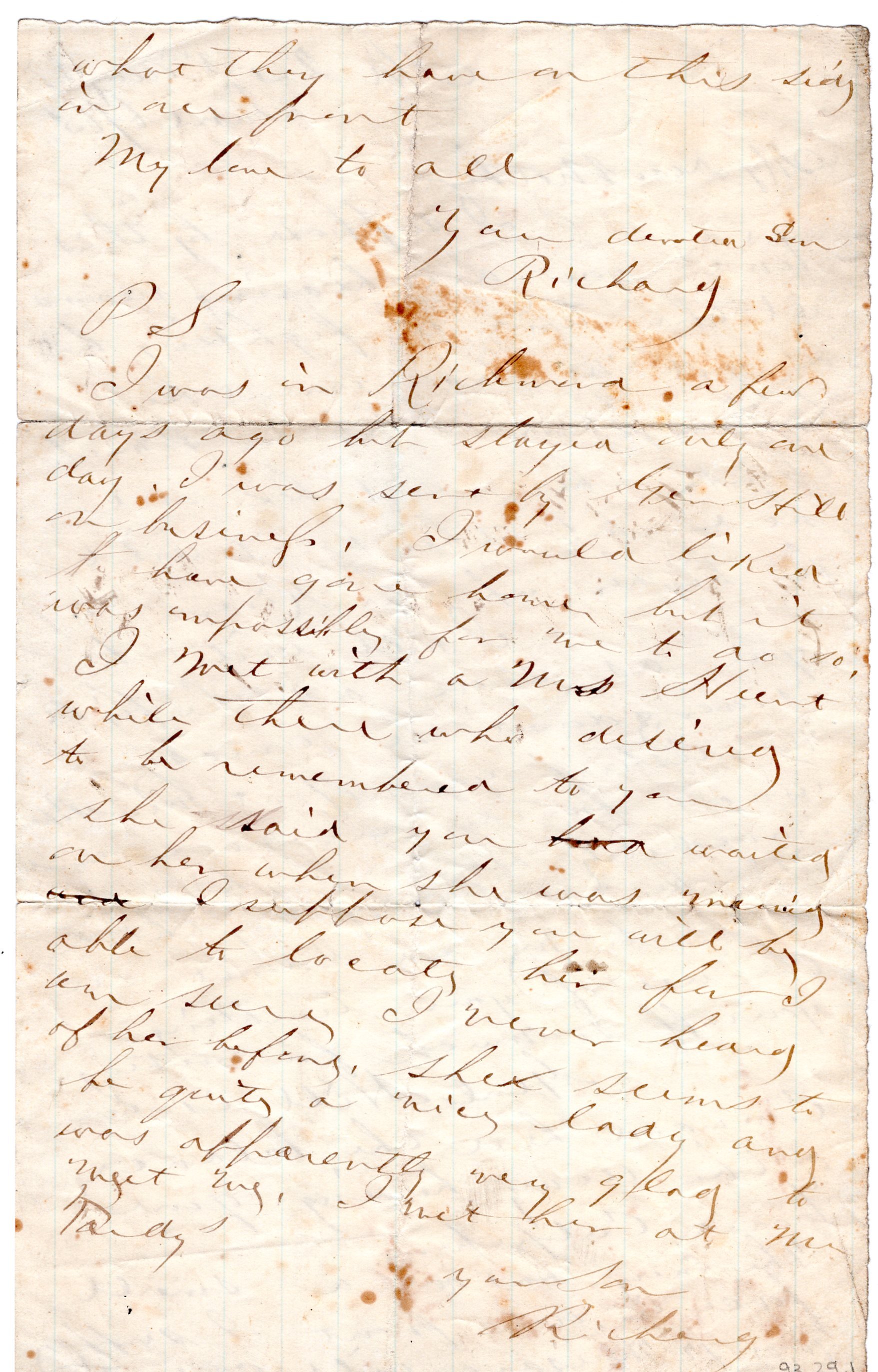

Letter from Richard Henry Toler Adams to his mother, 1863

Gift of Mrs. William Massie, 93.29.1

At the time of writing this letter, the 24-year-old Richard Henry Toler Adams was serving as a captain and a signal officer under A. P. Hill, whom he mentions in this letter. He is writing to his mother, Susan Elizabeth Duvall Adams, a daughter of Maj. William Duvall who served in the Revolutionary War under Patrick Henry. Like many letters home during the war, Adams reassures his mother that he is safe, healthy, and in good hands serving in the Confederate Army.

After the war, Adams started a successful business and a large family in Lynchburg where he remained until his death in 1900.

“Don’t be uneasy nor disheart yourself at newspaper rumors for they are never correct immediately after a fight…I do not see the use of troubling yourself so much for nothing.”

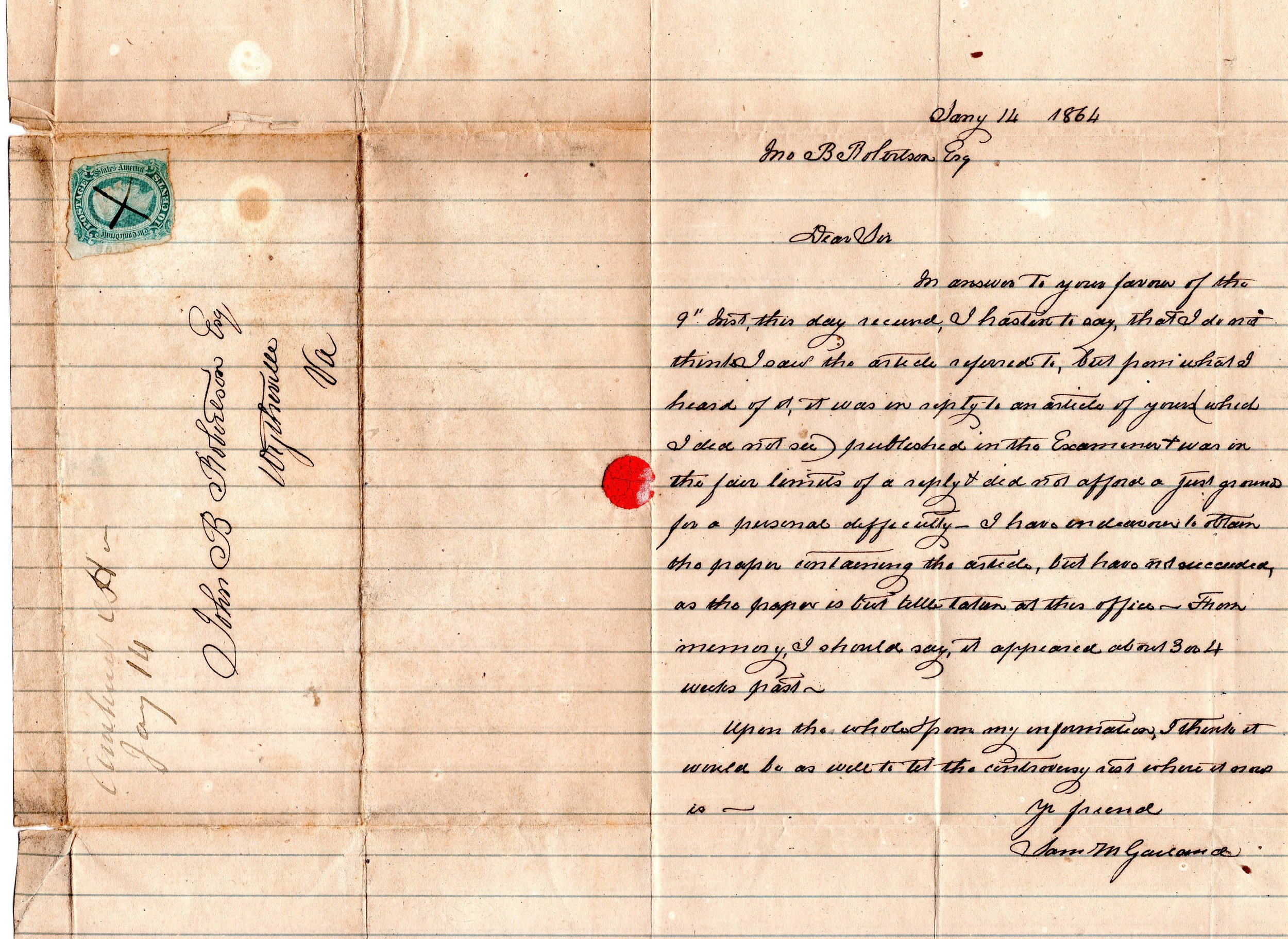

Letter from Sam Garland to John Robertson, 1864

Gift of Dr. Robert Gardner, 2005.2.24

Samuel Meredith Garland was a prominent lawyer and politician in Amherst County. At the time of the letter, Garland operated Kenmore Plantation where he enslaved dozens of individuals. As a politician, he served as the Clerk of Court for Amherst County which allowed him to get elected to the Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1850. The convention instituted even more draconian measures to keep the Black population of Virginia in bondage like increased taxes on enslaved individuals and prohibitions on manumissions by enslavers.

In this letter, Garland writes to John Robertson of Wytheville about a recent article in the Richmond Weekly Examiner. While we do not know the contents of the article or the nature of the “controversy,” we can gather that Garland may have had a history of issues with articles in the Examiner:

Garland sat the Virginia Secession Convention of 1861 where he voted for Virginia’s secession from the United States twice. Upon his death in 1880, his obituary described him as a, “States Rights Whig in politics.”

“Upon the whole of my information, I think it would be as well to let the controversy rest where it now is.”

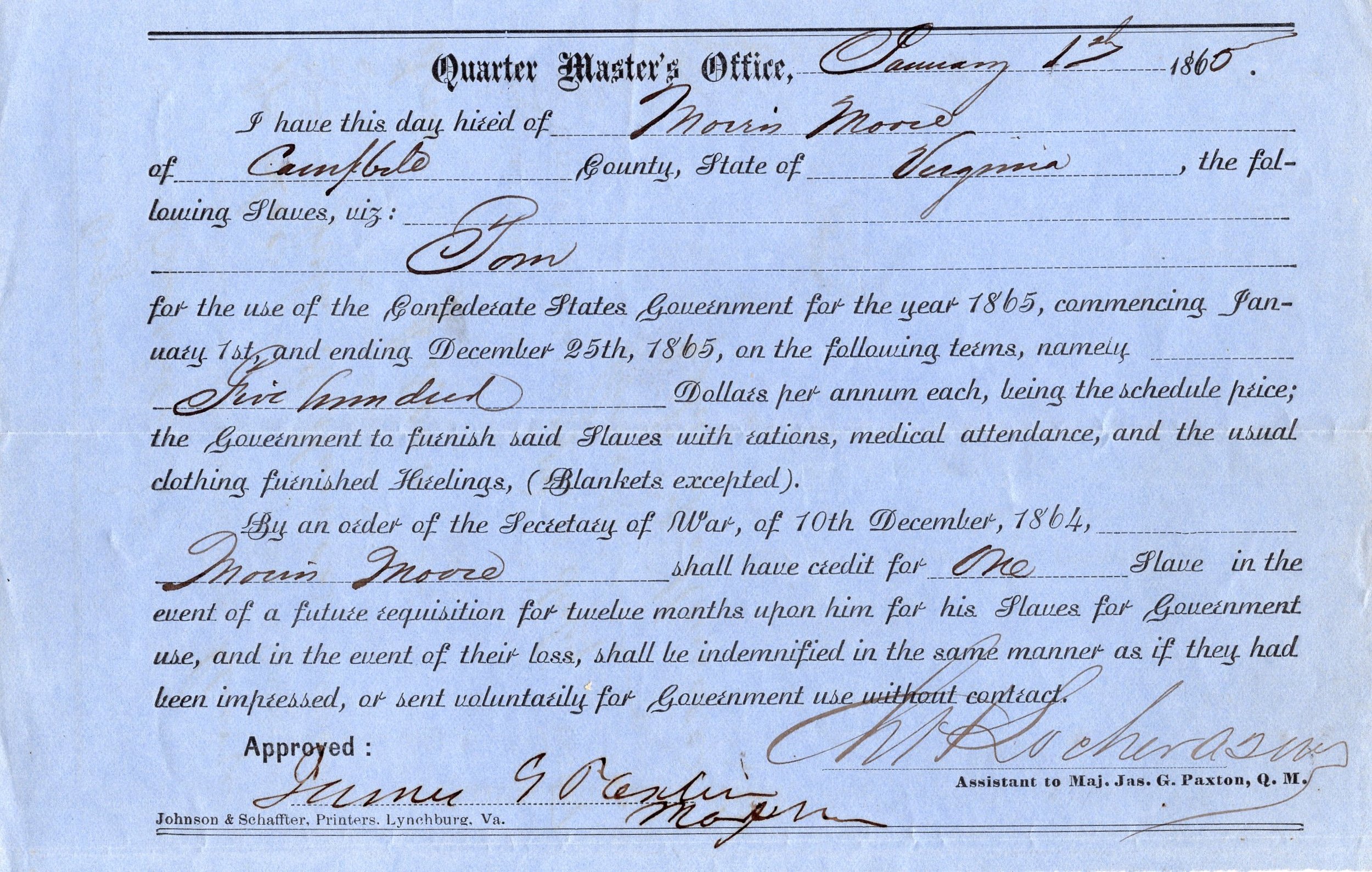

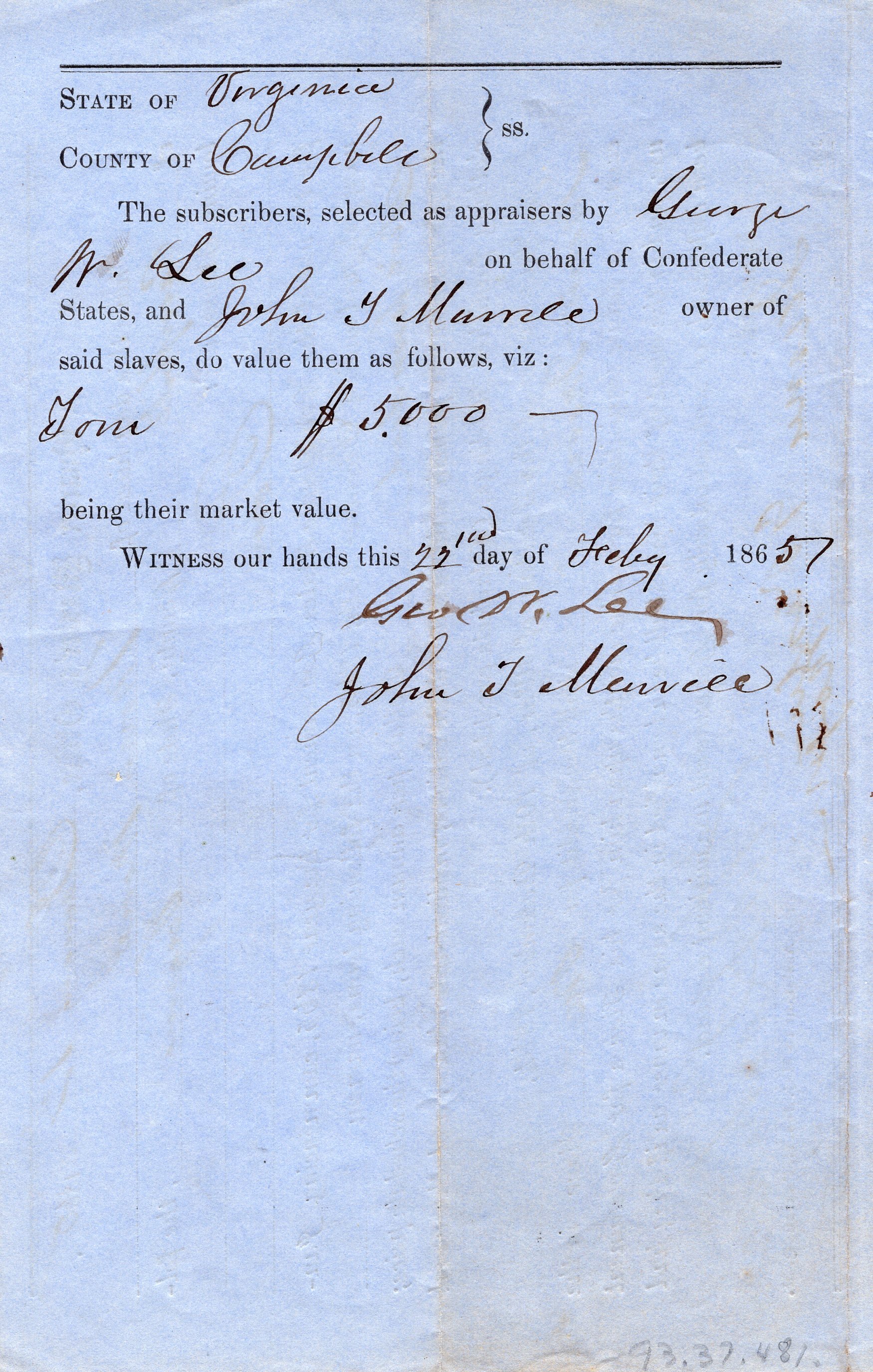

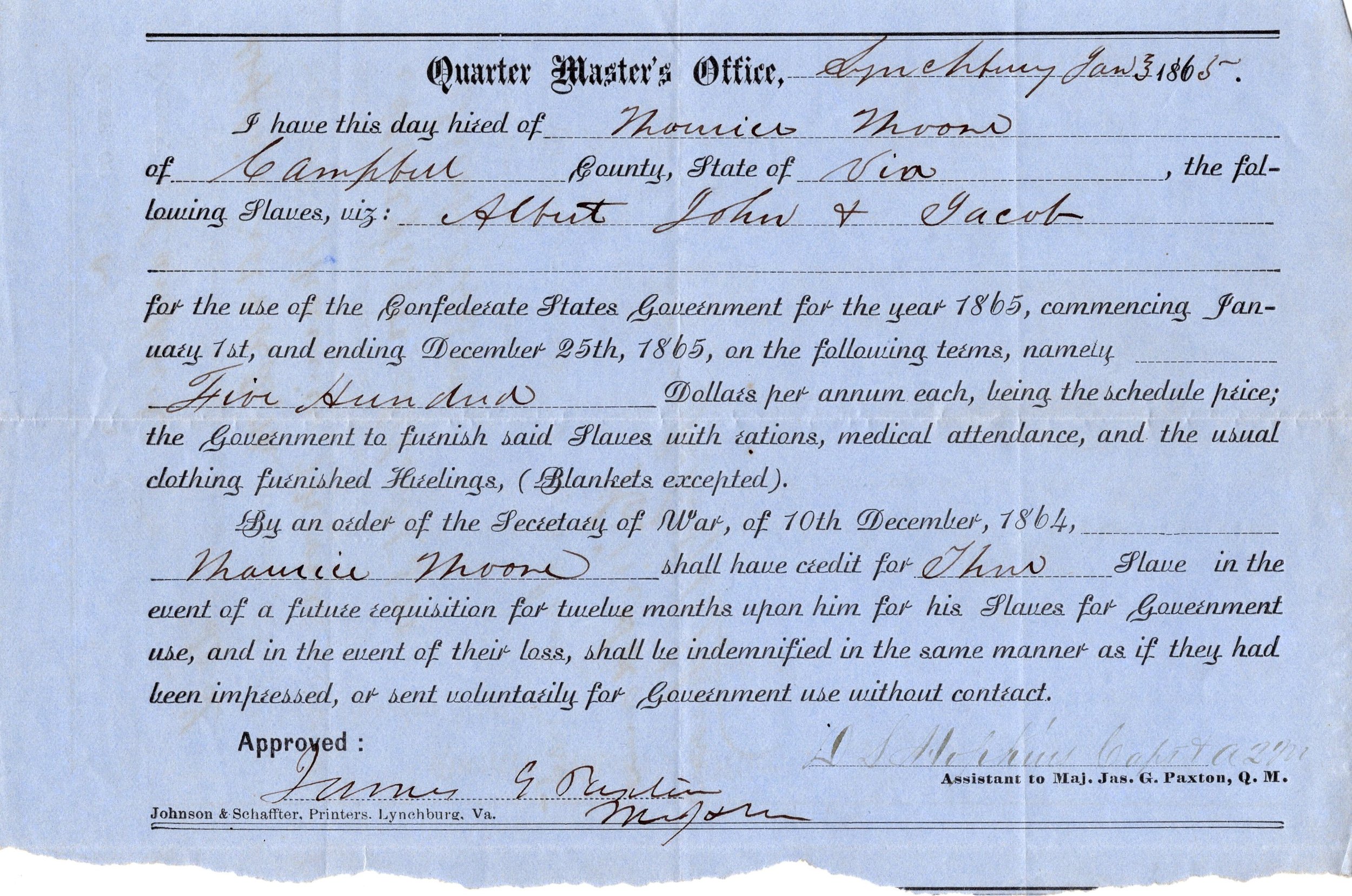

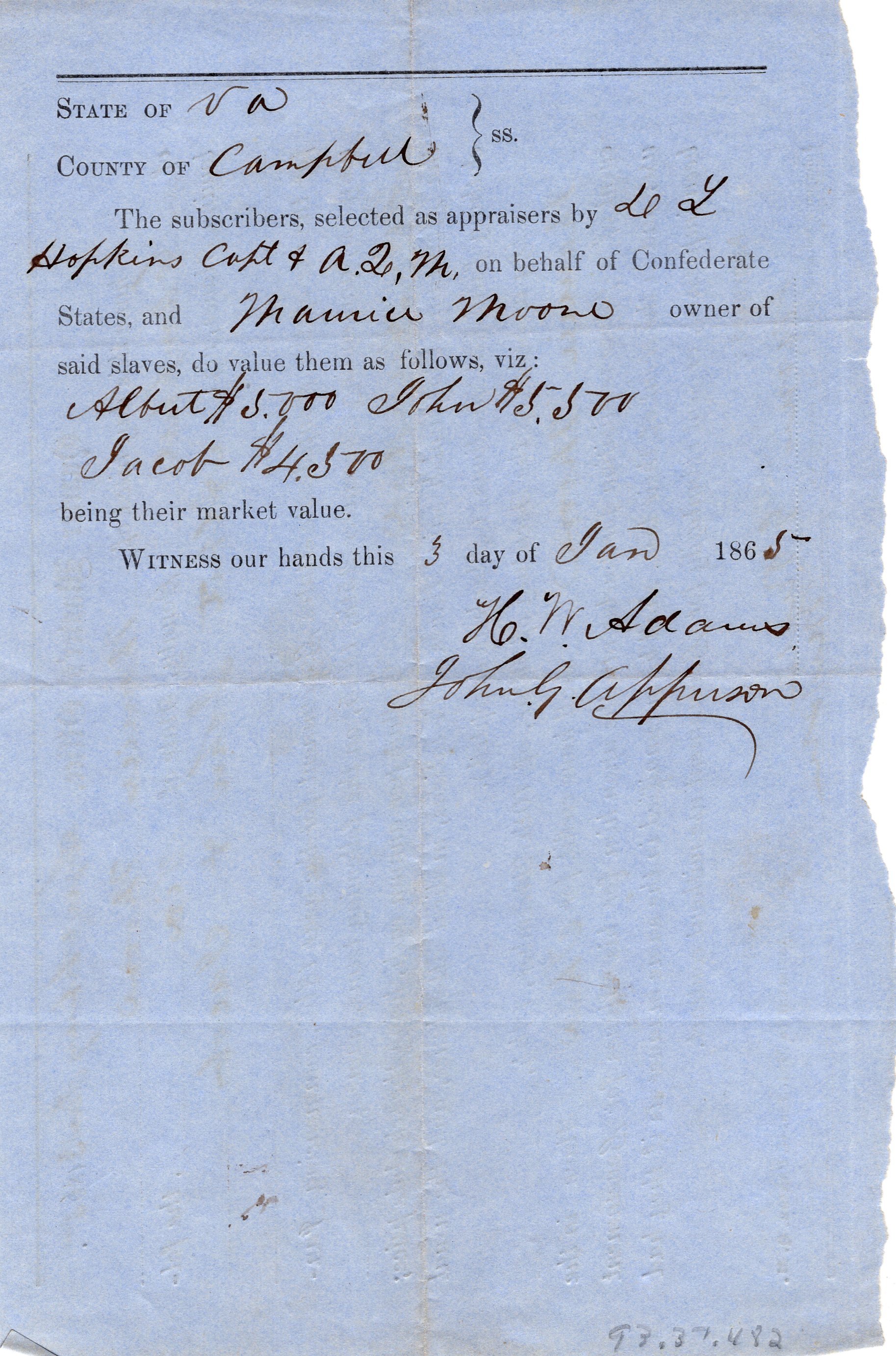

Contracts from the Confederate States of America to hire four enslaved men, 1865

Gift of Ida B. Younger, 93.37.481-482

These two documents portray the cruel banality of slavery in the South. The Quarter Master’s Office dealt with rations, transportation of supplies and lodging for Confederate military efforts. In these two contracts, we see that Tom, Albert, Jacob and John, all enslaved by Maurice Moore in Campbell County, were “hired” by the Confederate government to perform unpaid labor in the war effort to keep them enslaved. These contracts underline the primary goal of the Confederate States of America: to uphold the institution of chattel slavery.

Gen. Order #116 by Major General John Gibbon, 1864

Gift of Dorothy Wilson, 96.12.3

On the Union side of the Civil War, thousands of military orders carried information across battle lines. In this military order, 1st Lieutenant Presley Cannon was acquitted for two charges against his actions in the war. According to the testimony of Capt. Strawbridge, Lt. Cannon was ordered to prevent contact between picket lines. However, Cannon did not properly enforce this order which sent him to be court martialed.

Letter from Francis A. James regarding a freedom seeker named Jesse, 1854

Gift of Dorothy Wilson, 96.12.5

This letter from Francis A. James, an enslaver from North Carolina, wrote to an acquaintance in Lynchburg asking him to inquire about Jesse, a “fugitive slave” who presumably fled north. According to the Fugative Slave Act of 1850, if Jesse successfully crossed the border into a “free” state, that state must cooperate with the “slave” states to recapture him. This law further polarized the divide in the country over the issue of slavery, setting the stage for the Civil War a few years later.

James enlisted in the Confederate Army in 1862, but a few months later he sustained a serious gunshot wound that forced him to return home. We do not know what happened to Jesse.

“He left Canton on Tuesday morning along with some boats for [Lynchburg]...He exchanged all his clothes before he started so I can give no description of them…He has some free relations by the name of Armstrong living in Lynchburg.”

Colton’s map of “Middle Virginia,” date unknown

Gift of the Estate of James L. Owens, 2017.54.1

The Colton family produced hundreds of maps, atlases and guidebooks throughout the mid-to-late nineteenth century. This page shows central Virginia with the railroads highlighted in orange. You can see how significant Lynchburg was as the terminus of three rail lines, the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, the Petersburg and Lynchburg Railroad, and the Orange and Alexandria Railroad.

Gen. Order #77 by Maj. Gen. W. F. Smith, 1864

Gift of Dorothy Wilson, 96.12.10

In this military order, Maj. Gen. W. F. Smith requests additional half rations of whisky to be sent to another commander. During the Civil War, whisky served many purposes both as an intoxicating beverage and as a fortifying stimulant. Soldiers on both sides of the war developed strong dependencies on whisky, and their post-war addiction spurred women to mobilize the Temperance movement.

(above) Whisky bottle from a saloon in Lynchburg, c. 1906

Gift of Wayne Rhodes, 2015.18.3

In 1862, the U.S. Congress instituted a steep tax on whisky in reaction to the supply shortage during the Civil War. Prices skyrocketed and black market bourbon, moonshine and other spirits spread across the nation. Prices never returned to antebellum lows, but the demand remained high for decades after the war.

(left) Letter from S. S. Shint to Charles E. Dibble, 1865

Gift of Dorothy Wilson, 96.12.7

“Please telegraph me when the clothing is ready to issue to this command and I will send a [Sargent] to Lynchburg after it.”

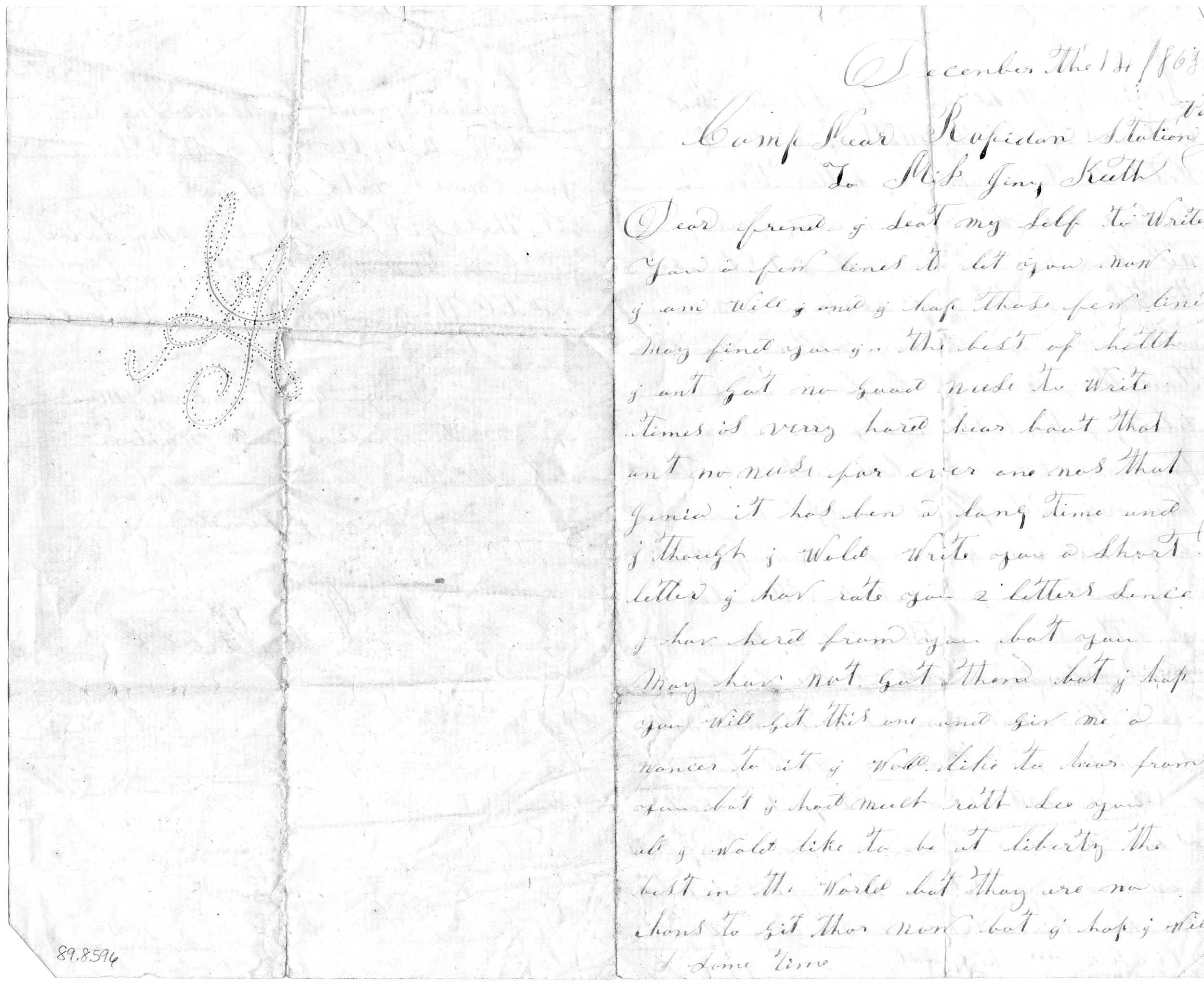

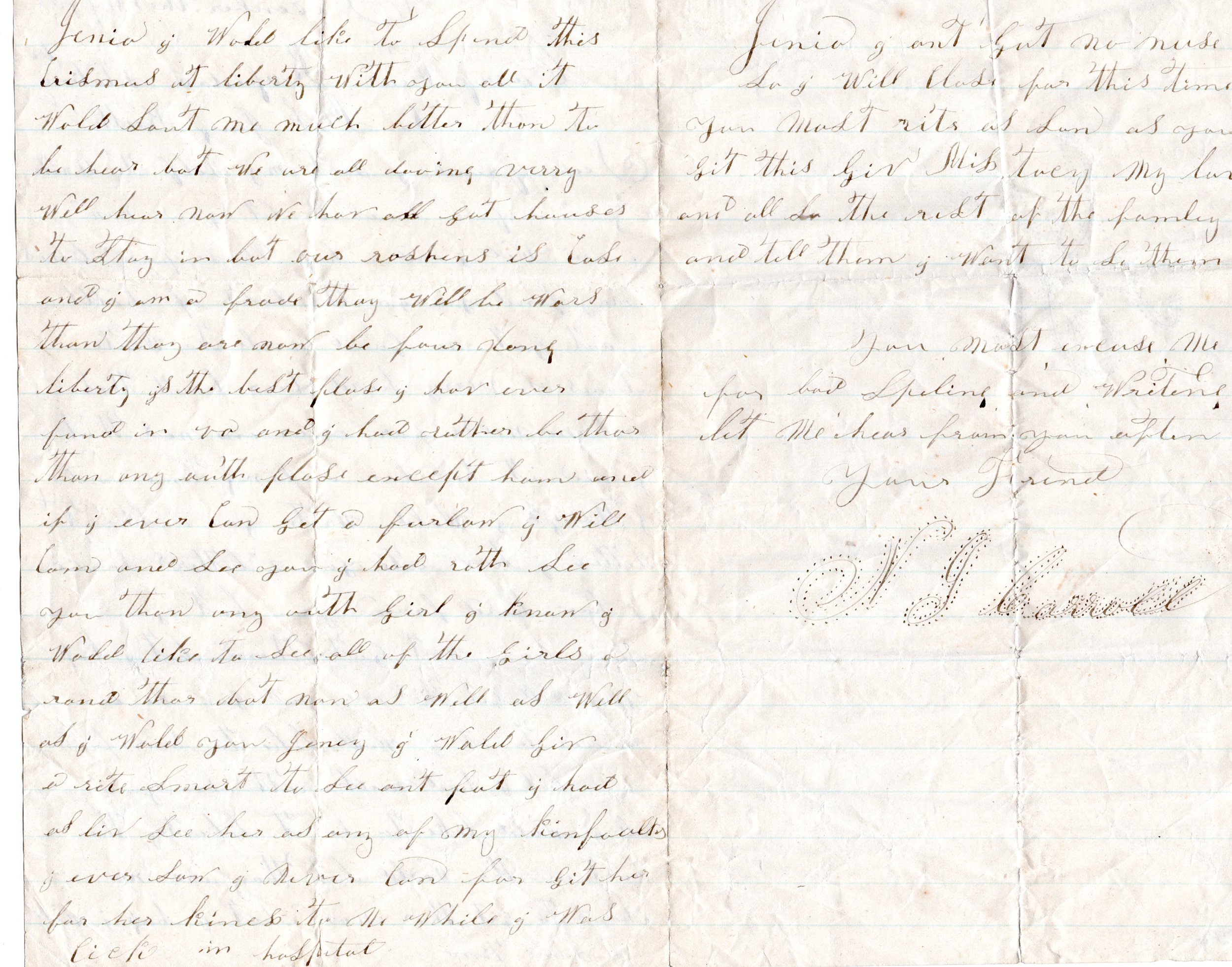

Letter from Nash J. Caroll, 1865

Gift of Rose McWane Kizer, 89.8.596

Correspondences between soldiers on the field and friends and family back home are the best ways historians have to understand what daily life during the Civil War was like. Nash J. Carroll, fighting on the eastern side of the Commonwealth, writes to Jenny Keith in Liberty (now Bedford) about his living conditions during the war.

Carroll survived the war, married, (not to Jenny) and raised a family in Bedford County. We do not know what happened to Jenny.

“Jenny, I would like to spend this Christmas at Liberty with you all. It would suit me much better than to be here, but we are all doing very well here now. We have all got houses to stay in but our rations is bad and I am afraid they will be worse than they are now”

Share Your History!

Do you have Civil War documents related to your ancestors? Do you have any photographs, memorabilia, or letters from Lynchburg during the Civil War? We would love for you to share them with us! The Lynchburg Museum System is actively seeking material to illustrate the full history of our city.

Call (434) 455-6226 or email museum@lynchburgva.gov