Exhibit Curated by Lynchburg Museum Staff

Digitized by Austin Gaebe

Virginia University of Lynchburg

In May of 1866, Rev. Philip F. Morris of Lynchburg's Court Street Baptist Church first proposed the construction of a seminary at the annual Virginia Baptist State Convention. The Convention chose the City of Lynchburg as the site due to its central location, large Black population, and its role as the terminus of three railroads providing numerous opportunities for Black employment. In 1888, the first bricks were laid for Lynchburg Baptist Seminary on Garfield Avenue, just over 1.5 miles from downtown.

The founding of a seminary for the training of Black ministers was an answer to a highly contested debate over the role of higher education in the advancement of the Black individual within post-Civil War American society. Some within the Black community, including the founders of Lynchburg Baptist Seminary, believed in self-reliance and emphasized self-help. Meanwhile, others argued for a gradual approach to advocating for their civil liberties. As historian Joseph Brummell Earnest wrote in his 1914 dissertation The Religious Development of the Negro in Virginia, Virginia Seminary was a school “of the Negroes, by the Negroes and for the Negroes.’’

Under the leadership of their founding president, Rev. Morris, the school’s mission was primarily to train ministers, although it also offered co-ed, secondary classes. Morris retired in 1891 and Gregory W. Hayes became the next president. President Hayes led the school in a new direction and the institution became both a college and seminary. It also operated largely independent of funding from white donors and organizations, and by extension, white control. Over the years, the school grounds expanded, sports programs were instituted, and the school even managed a farm in Campbell County to augment the cost of feeding students.

VUL remains Lynchburg’s oldest institution for higher education and the city’s oldest institution associated with African American education. Notable alumni include poet Anne Spencer, Malawi leader John Chilembwe, and civil rights activists Vernon Johns and James Robert Lincoln Diggs.

History of Names

Lynchburg Baptist Seminary (1886–1890)

Virginia Seminary (1890–1900)

Virginia Theological Seminary and College (1900–1962)

Virginia Seminary and College (1962–1967)

Virginia College-Virginia Seminary (1967–1996)

Virginia University of Lynchburg (1996–present)

Course Catalogue from Virginia Theological Seminary and College, 1920-1921

Courtesy of Ted Delaney

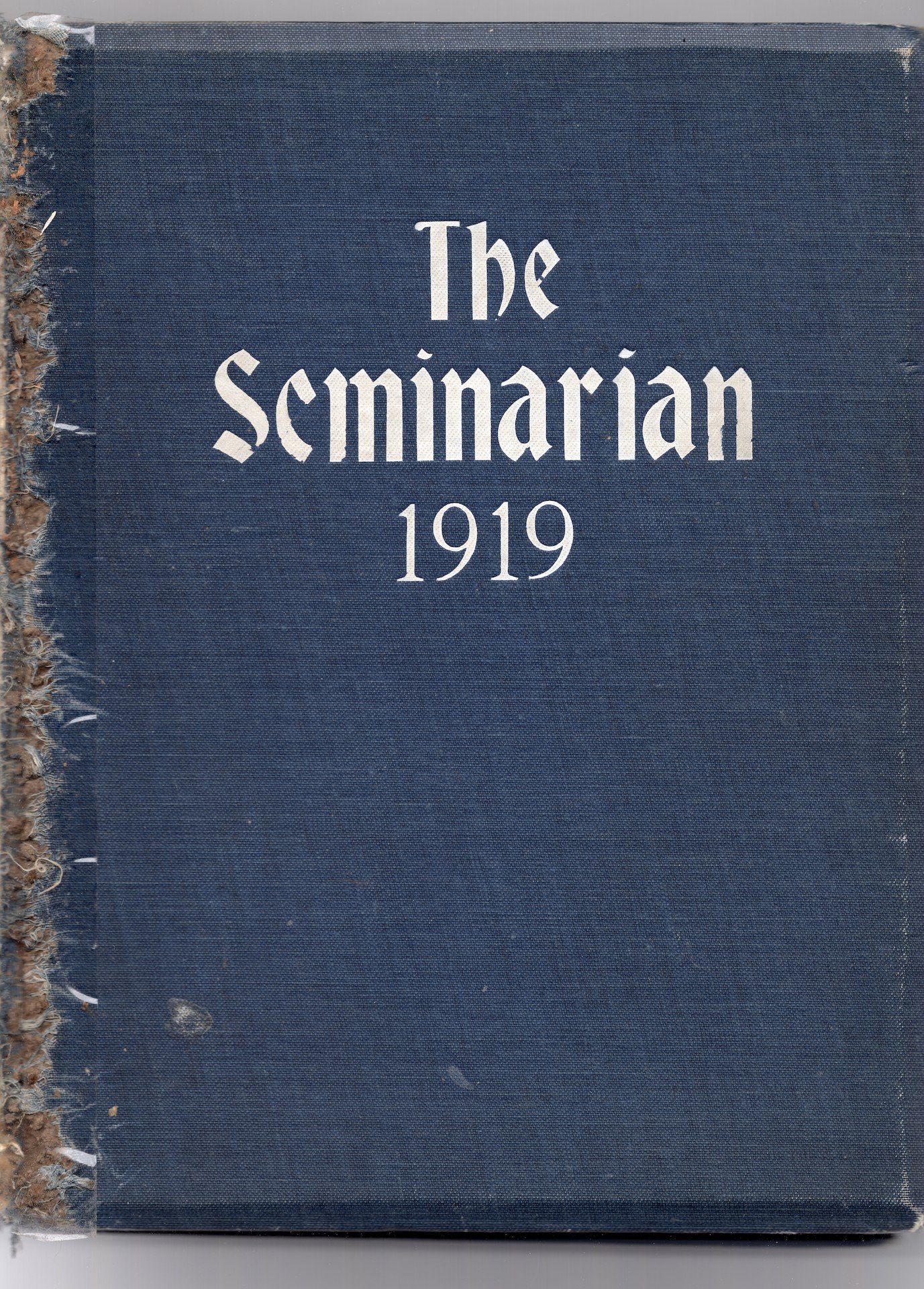

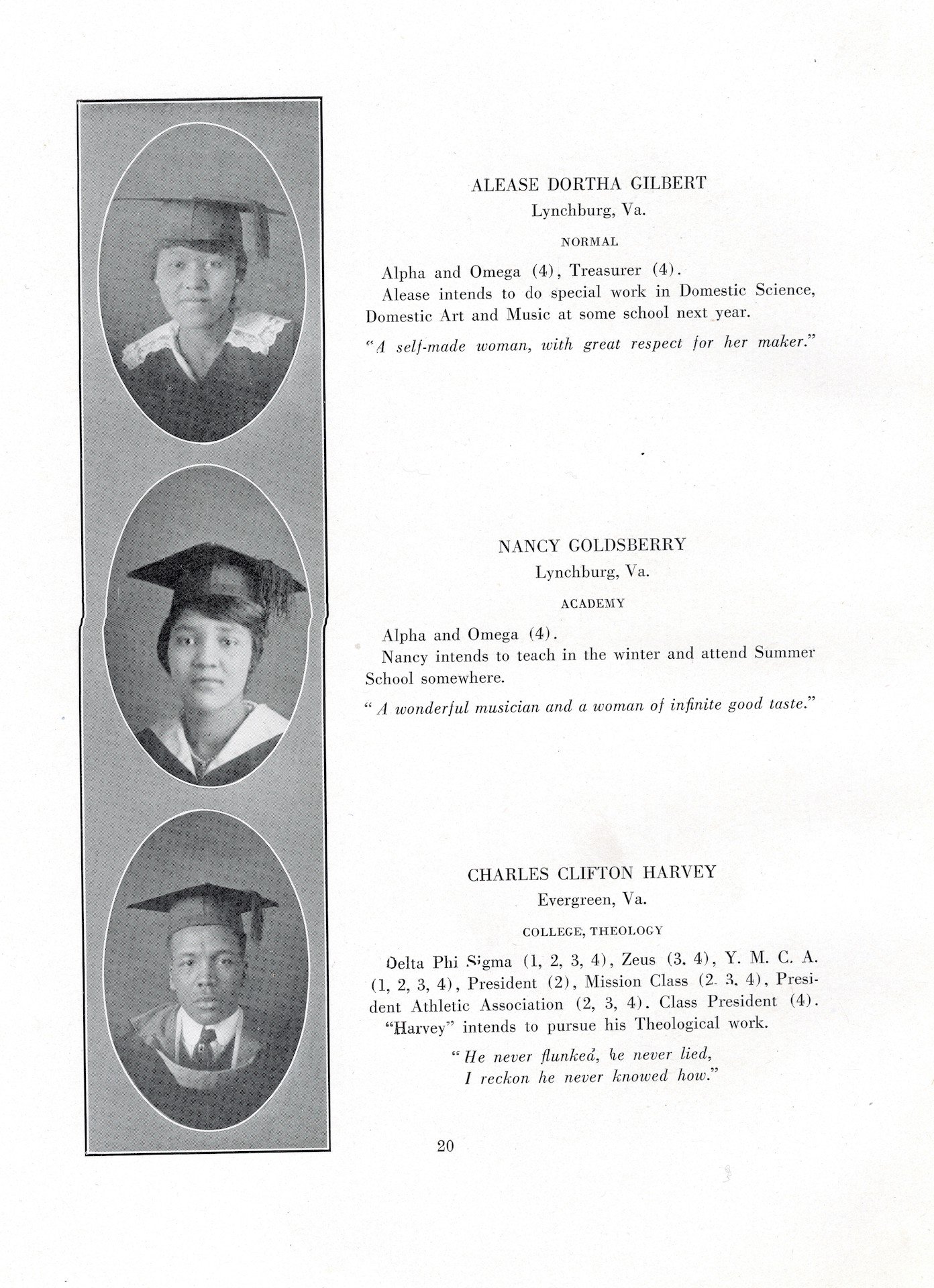

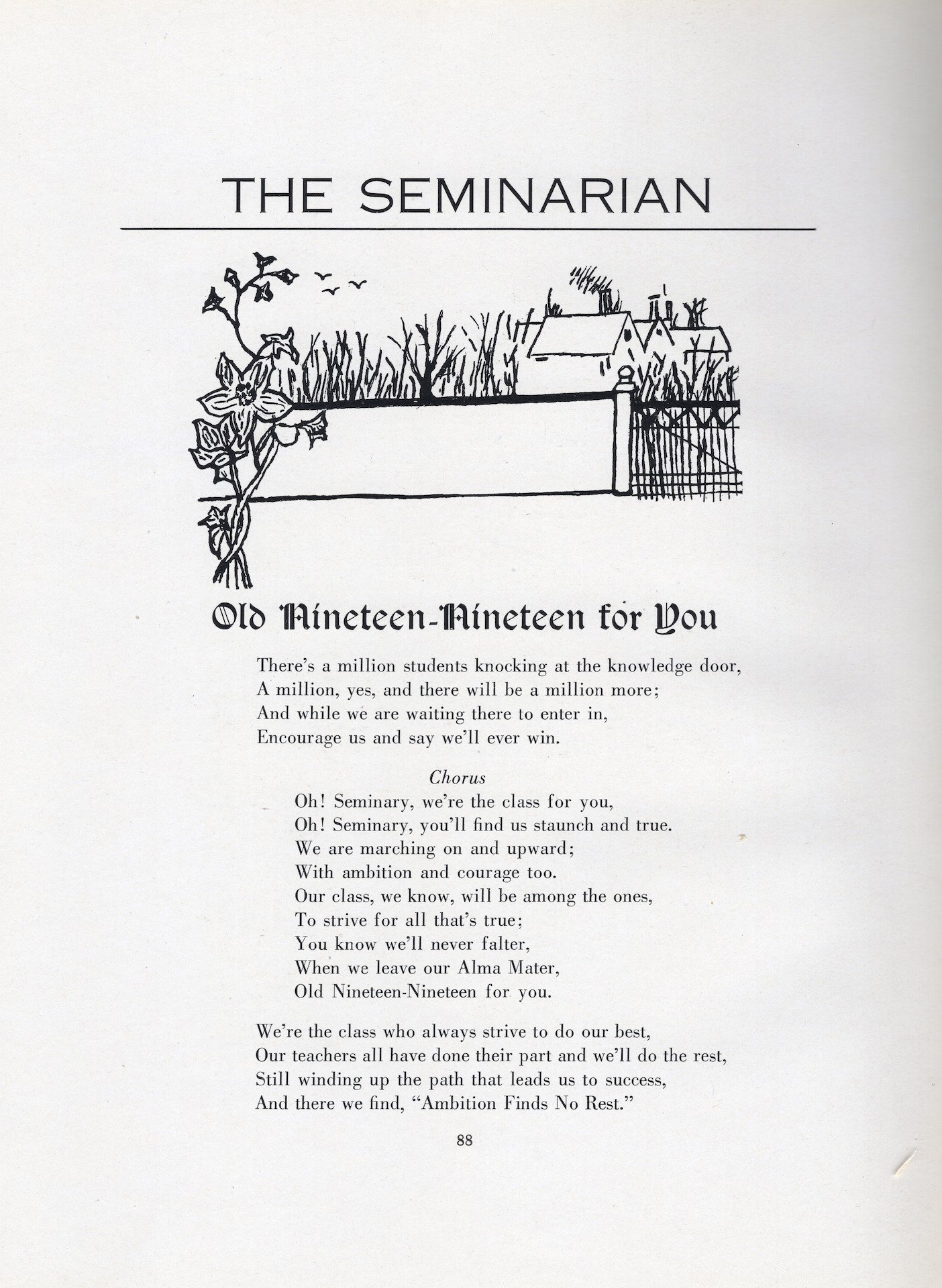

Seminarian Yearbook from Virginia Theological Seminary and College, 1919

Courtesy of Ted Delaney

Diploma for Blanche Arthur from Virginia Theological Seminary and College, 1916

Gift of Raymond Davies, 96.30.1

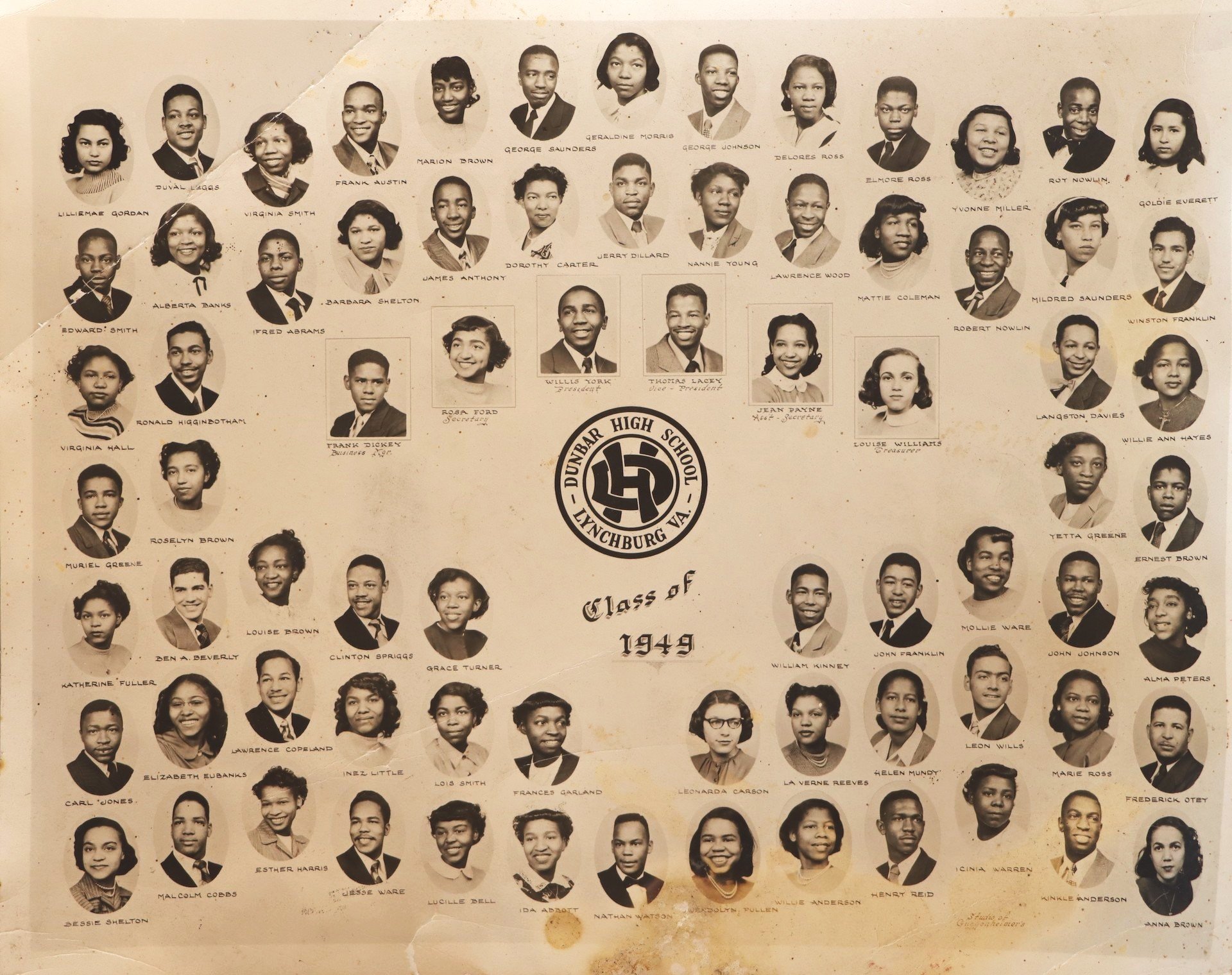

Dunbar High School

Lynchburg’s Paul Laurence Dunbar High School opened in 1923 and is located on 12th Street in historic downtown Lynchburg. Initially, the school was created by the all-white school board at the request of the Black community for a new Black high school. In the beginning, the school offered four years of English, History, Math, Science, and Latin, and had a high success rate of sending graduates to college. Because it was a school for African American students, many of the amenities offered to white students were not available. Parents provided school lunches rather than the state; the library consisted of discarded books from Jones Memorial Library and librarian Anne Spencer’s private collection; and the community provided many supplies and equipment rather than Lynchburg’s school system.

The first principal of Dunbar High School was William F. DeBardeleben who had previously been principal of Jackson Street High School and was the first Black school principal in Lynchburg. Because he was African American, the Lynchburg Public School System decided that he would have a supervising principal who was white. James Mozee served as the second principal of Dunbar in 1932, also under the supervision of a white principal. In 1938, Clarence Williams “C.W.” Seay became the first Black principal without a white supervising principal and he held the position for 30 years. Seay was an influential leader in Lynchburg and pressured city leaders to hire Black educators, personnel, and administrators for the school. He improved Dunbar’s curriculum, extracurricular activities, and expanded the opportunities for students. By the time Seay retired in 1968, Dunbar was one of the top Black high schools in the segregated South. After leaving Dunbar, Seay went on to be a professor at the University of Lynchburg, a member of City Council, and ran for Mayor.

In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled that school segregation was unconstitutional in the decision Brown v. Board of Education. In the 1960s, Lynchburg attempted to integrate Dunbar’s Freshman and Sophomore classes with white students, but the decision was met with many objections. After 16 years of lawsuits and attempts to desegregate the city’s white high school, E.C. Glass, Dunbar High School closed its doors and the students were integrated into white schools.

The building stood empty until 1994 when the Paul Laurence Dunbar Middle School for Innovation opened as part of Lynchburg City Schools.

Left: Dunbar Chronicle Student Newspaper

Gift from the Estate of Dorothy M.L. Obey, 99.42Above right: Dunbar High School Drum Major and Majorettes, 1948-1949

Dunbar collection, Gift of Carolyn BrownBelow right: Dunbar High School’s First Band, 1948-1949

Dunbar collection, Gift of Carolyn Brown

Virginia Collegiate & Industrial Institute

In 1893, the Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute opened on Seabury Avenue near the current location of William Marvin Bass Elementary School. It was the second Black institution for higher education in the city and offered college preparation, industrial education, and teacher training. The college was supported by both Jackson Street Methodist Episcopal Church and the Freedmen’s Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church. Their first principal was Professor Frank Trigg, a well-known Black educator in Lynchburg. Another prominent principal was Reverend George E. Stephens. He was married to Lucy Bolding Stephens, one of the first African American women to register to vote in Lynchburg.

The school was closed in 1917 after a fire destroyed the main building.

Right: Remains of Virginia Collegiate and Industrial Institute, circa 1949-1951

Lynchburg City Schools, 2011.41.9

Above: Jackson Street Elementary School, circa 1890-1920

Lynchburg City Schools, 2011.41.38

Jackson Street High School (Lynchburg Colored High School)

From 1905 to 1925, the Jackson Street School offered an opportunity for education to Lynchburg’s African American high school students. It originally operated inside Jackson Street Methodist Church at 901 Jackson Street. In 1911, the Yoder School building was completed on Jackson Street between First and Second Streets giving the students a separate space.

When Dunbar High School opened in 1923, the students from Jackson Street were transferred there and the Yoder School became an elementary school. The Yoder School building was demolished in 1970.

Payne School

Built in 1885, the old Robert S. Payne School originally stood at the corner of Polk and 12th Streets. It was an early public school specifically for African American students. Its namesake, Dr. Robert Spotswood Payne, was the chairman of Lynchburg City Schools at the time of construction. In the early 1950s, the school was demolished to expand Dunbar High School and the students were transferred to the old Robert E. Lee Junior High School, which was built in 1925. That location is currently Robert S. Payne Elementary School standing near 12th and Floyd Streets.

Polk Street School

The Polk Street School was officially founded in 1870 by the Black community with help from the Freedmen’s Bureau, before the Lynchburg Public School System existed. The building had formerly been one of the barracks buildings at the Confederate Camp Davis in the 900 block of Polk Street and was known as the “first free school for hundreds of miles around.”

Educator Amelia Perry Pride organized the McKenzie Sewing School within the building to further the domestic education of young students. She also established a cooking school on Madison Street and both were absorbed into the Lynchburg Public School System. The Polk Street School closed around 1910 and a building on Dunbar Middle School’s campus is named in honor of Amelia Perry Pride.

Top right: Annual High School Report from Jackson Street School, 1922- 1923

Dunbar collection, Gift of Carolyn BrownMiddle right: Payne Elementary School, formerly known as the Robert E. Lee Junior High School, circa 1920s

Gift of Troy Deacon, 2015.5.1Bottom right: Amelia Perry Pride with the last class of the Polk Street School, circa 1910

Lynchburg Museum System collection, 2019.42.1

Share Your History!

Do you know someone who attended or taught at an all-Black school or college in Lynchburg? Do you have any photographs, memorabilia, or documents from your time as a student or educator? We would love for you to share it with us! The Lynchburg Museum System is actively seeking material to illustrate the full history of our city.

Call (434) 455-6226 or email museum@lynchburgva.gov