Exhibit Curated by Catherine Dalton

Digitized by Austin Gaebe

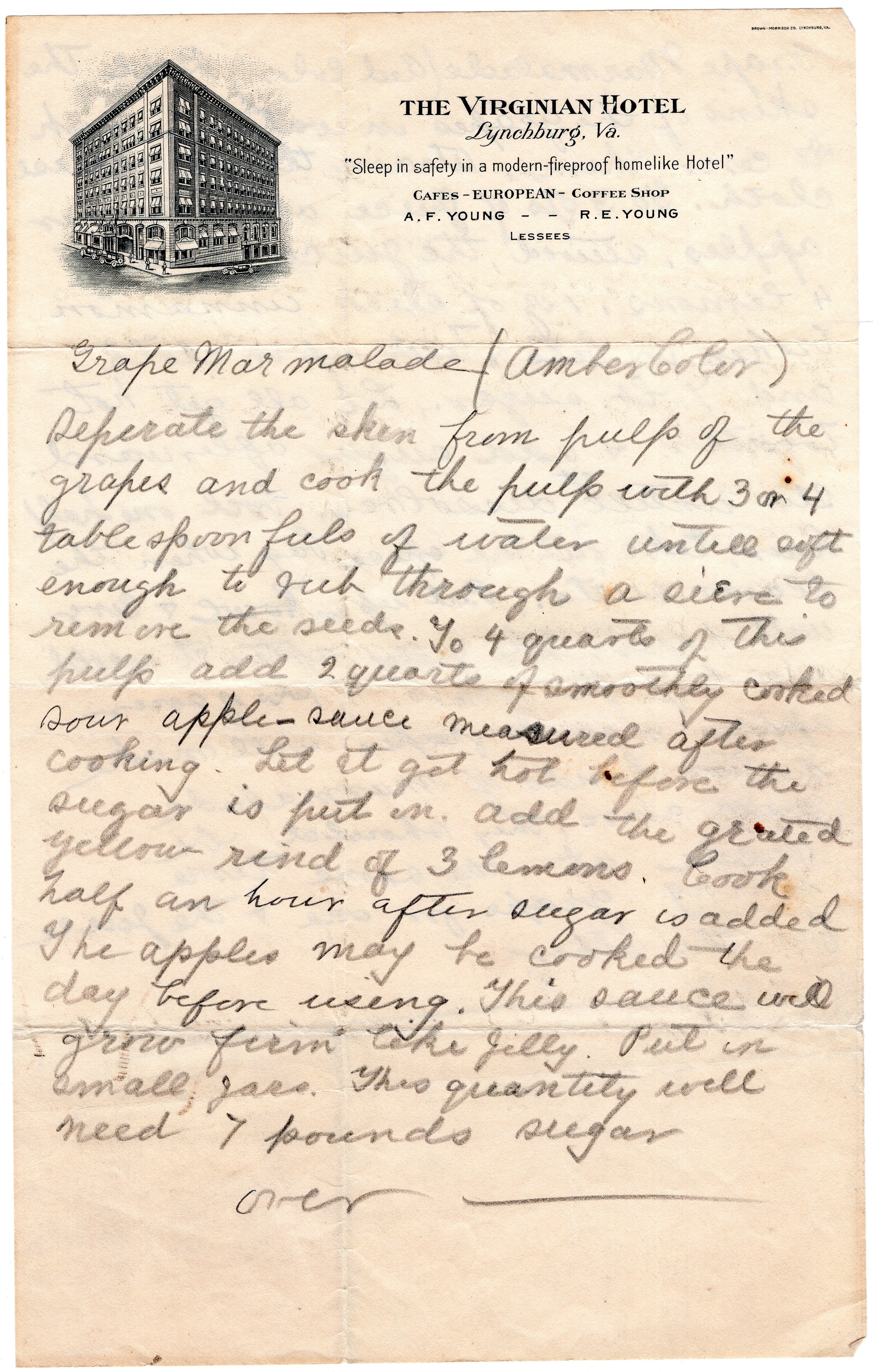

Have you wondered why there are so many word processing fonts available? Before texting on a phone, computers, typewriters, and printing presses, there was handwriting. As with fingerprints, no two persons write the same way. Since writing was developed thousands of years ago, handwriting has become an integral part of the way people communicate. It has been used in correspondences, legal documentation, personal notes, journals, and more.

Today, most people rely on typed communication like texts or emails. Handwriting (specifically cursive) is used less in our modern world and was even removed from the Common Core curriculum for schools in 2015. Cursive has recently seen a resurgence in classrooms and has always been included in Virginia’s Standards of Learning.

Handwriting is useful in many ways, despite the overwhelming availability of typing technology. Handwritten notes help students remember lessons better; handwritten memos and journals are more secure than some technology; and even mail publishers have started using fonts that mimic handwriting knowing that the envelope is more likely to be opened.

Perhaps the most important reason people still use handwriting today is the personal touch it brings. People still handwrite notes to loved ones, make meaningful comments in the margins of recipe books, write postcards to family at home, and much more.

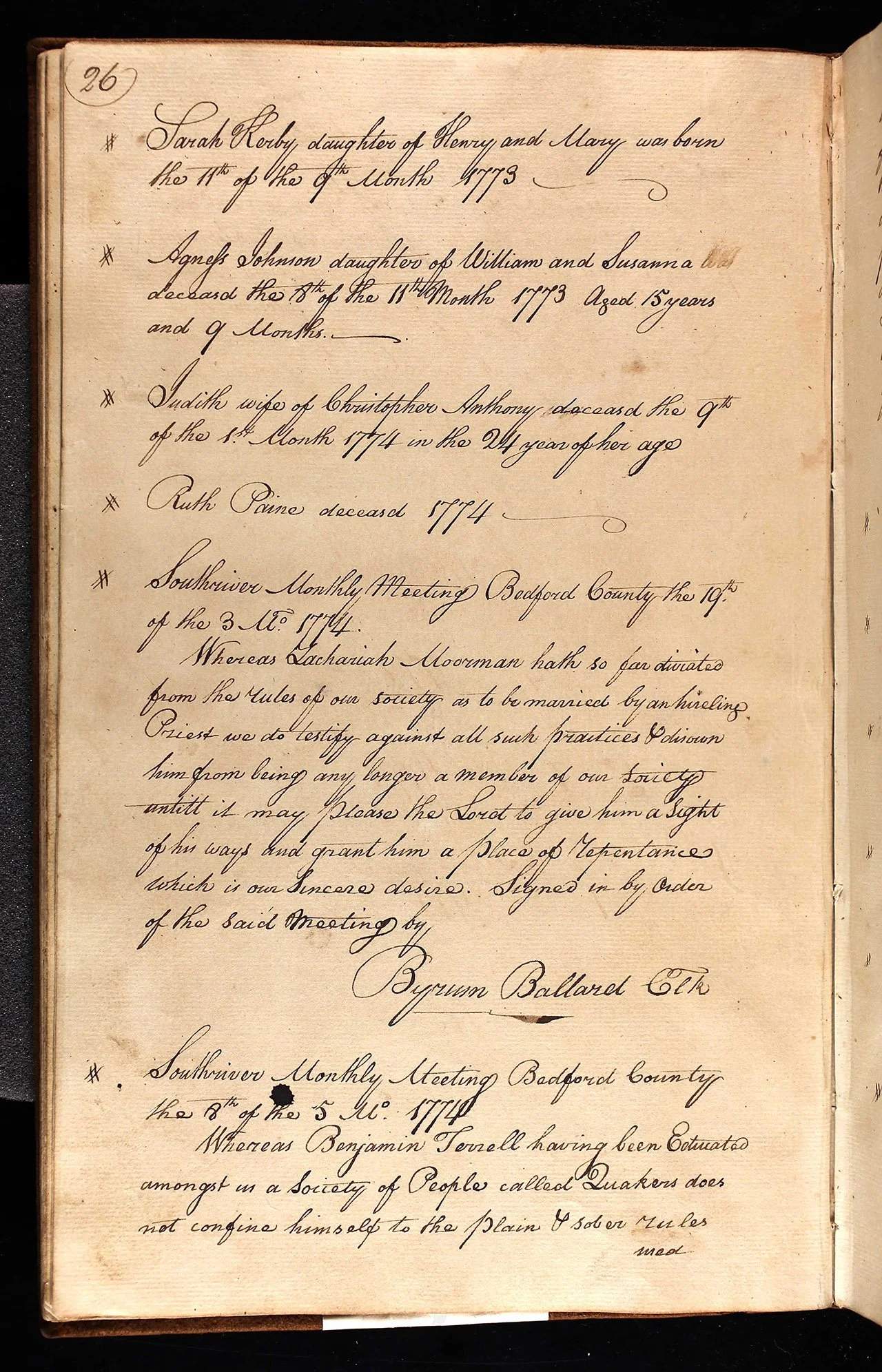

Some of the earliest known examples of handwriting from the Lynchburg area are the record books of the South River Quaker Meeting. This particular page, handwritten by Clerk Byrum Ballard, records member births, deaths, and discipline from 1774.

Courtesy of Ancestry.com (U.S. Quaker Meeting Records, 1681–1935)

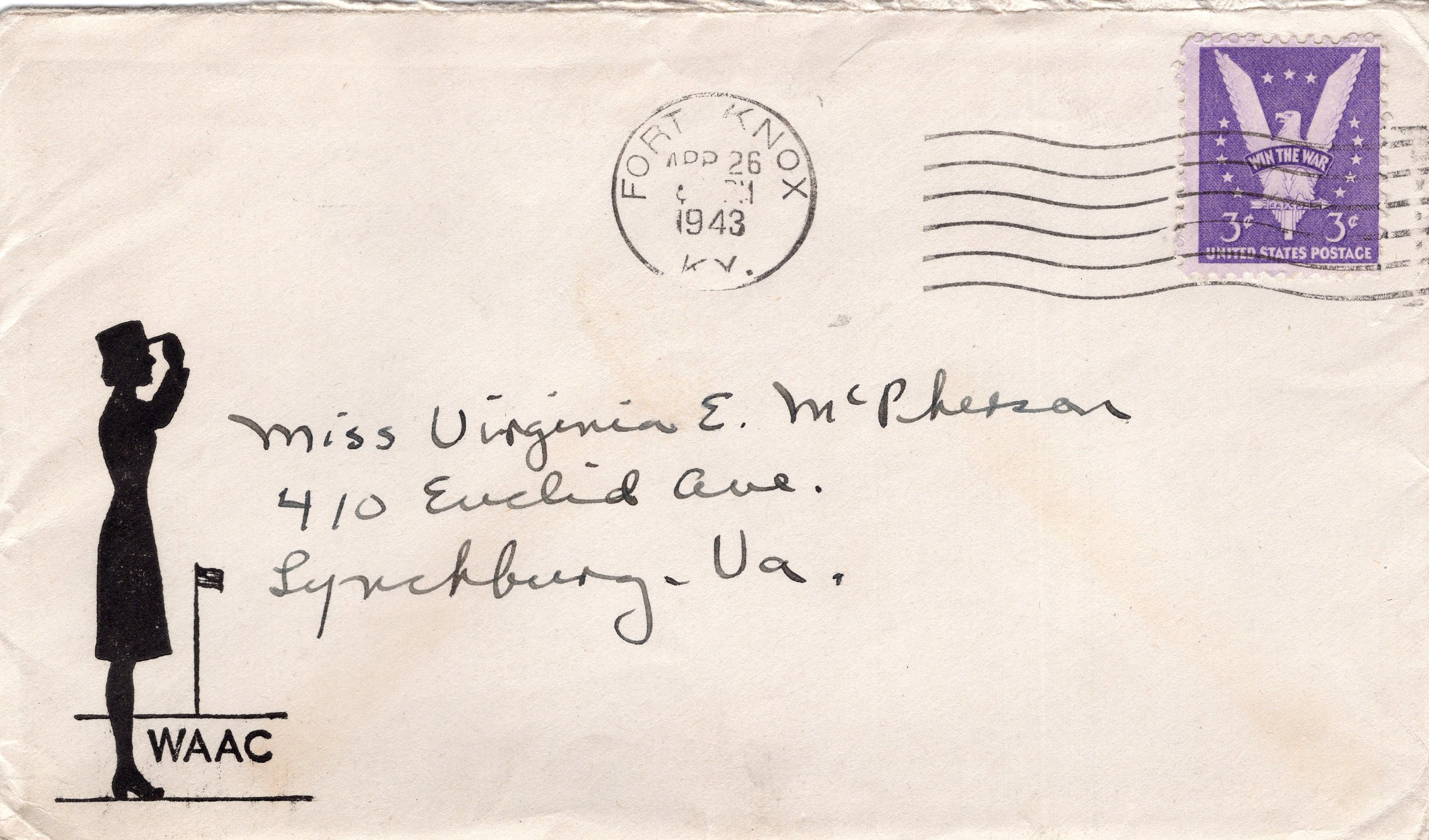

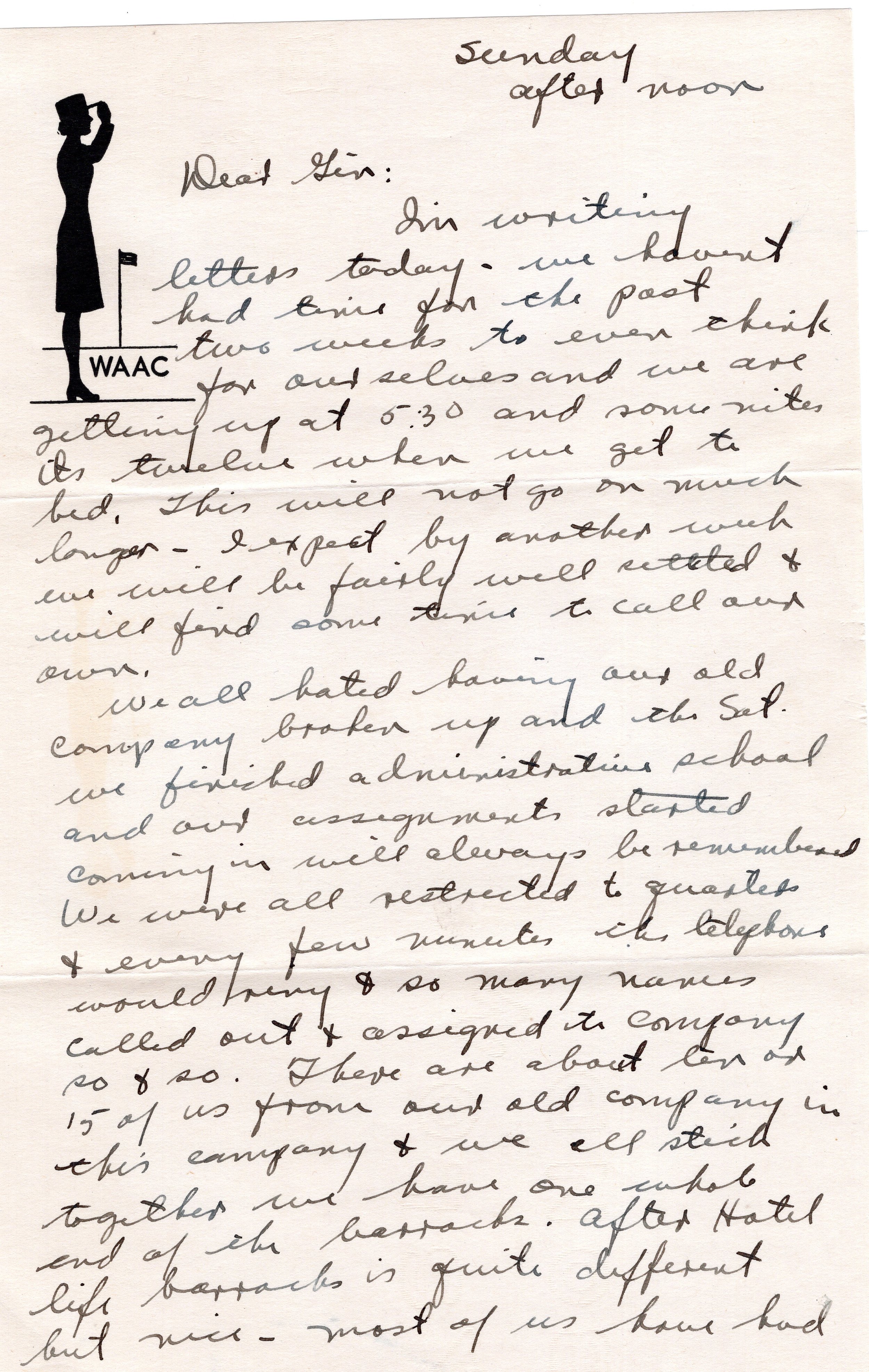

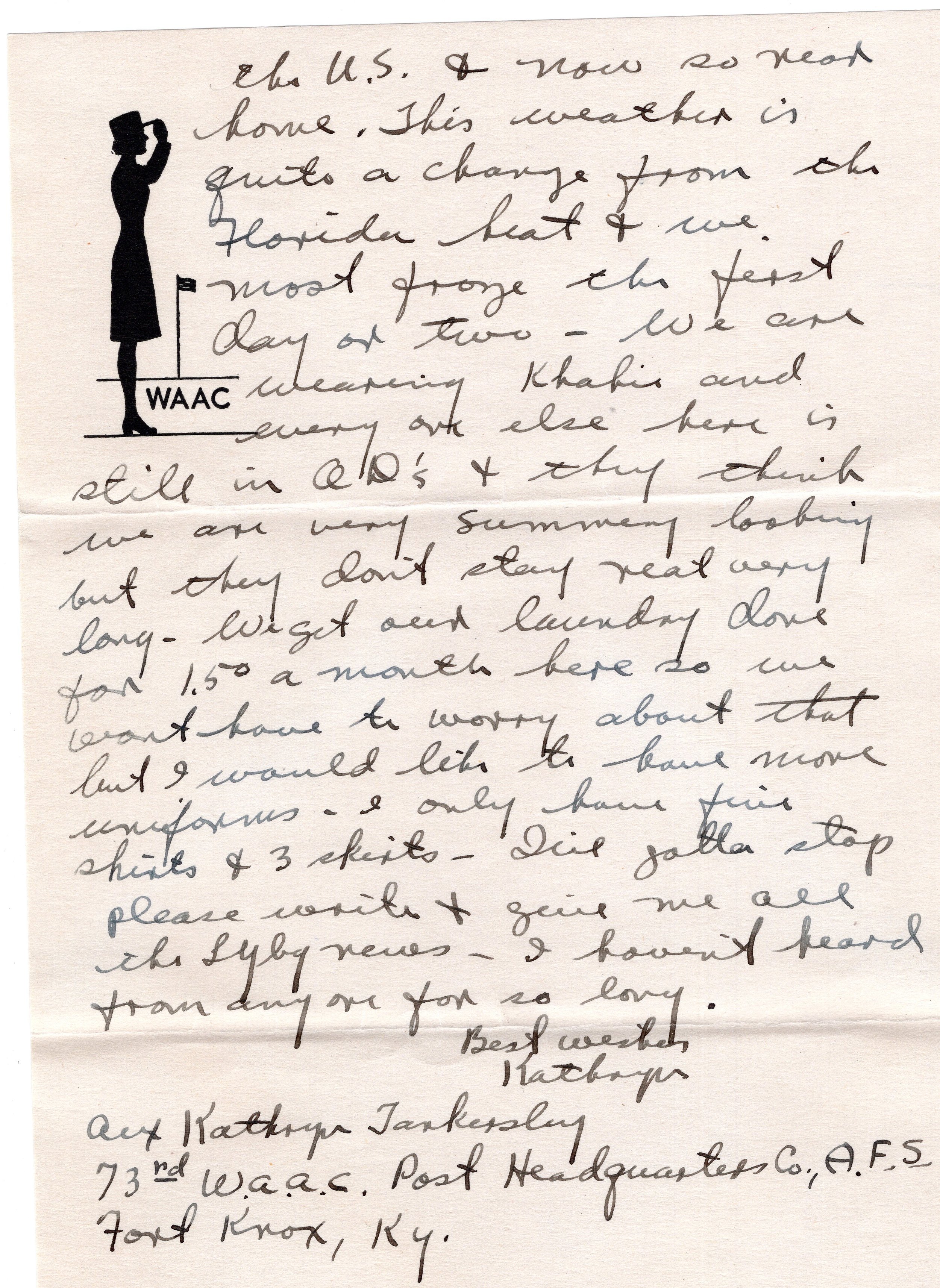

Katheryn Tankersley was born in 1906. She lived at 1111 Rivermont Avenue until she enlisted as an aviation cadet in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) in 1942, the same year it was founded. The Corps is the women’s branch of the U.S. Army. WAAC was established "for the purpose of making available to the national defense the knowledge, skill, and special training of women of the nation." On July 1, 1943, WAAC was given active duty status, becoming Women's Army Corps (WAC).

Nearly 150,000 American women served in the Women’s Army Corps during World War II. Many of these women served throughout the world with the Army Ground Forces, the Army Service Forces, and the Army Air Forces, in a variety of supporting, non-combat roles. The majority of WACs served with the Army Service Forces.

Tankersley was discharged in 1945 and returned to Lynchburg to live at 507 Euclid Avenue, near her friend Virginia McPherson, to whom this six page letter is written.

Letter: Gift from the Estate of Virginia and Ruth McPherson, 2005.42.85a

Portrait: Gift from the Estate of Virginia and Ruth McPherson, 2005.42.90a

Francis (Frank) Carter Scruggs was commissioned as a soldier of the Third Regiment Infantry of the Virginia Volunteers in 1898. The Virginia Volunteers was organized in 1881 and included men from Lynchburg, Danville, Charlottesville, and Alexandria among others. In 1898, they were mustered into Federal Service and participated in the Spanish American War.

Gift of Mrs. D. F. Dinsmore Scruggs, 88.16.26

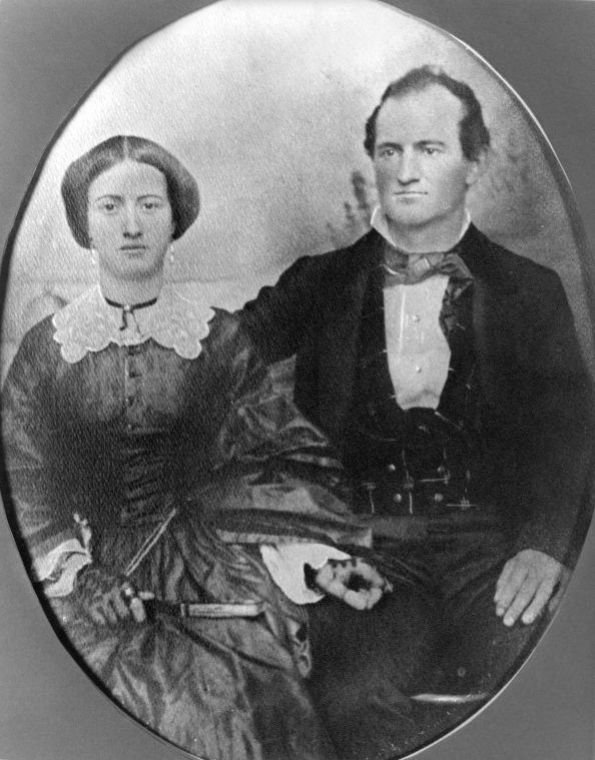

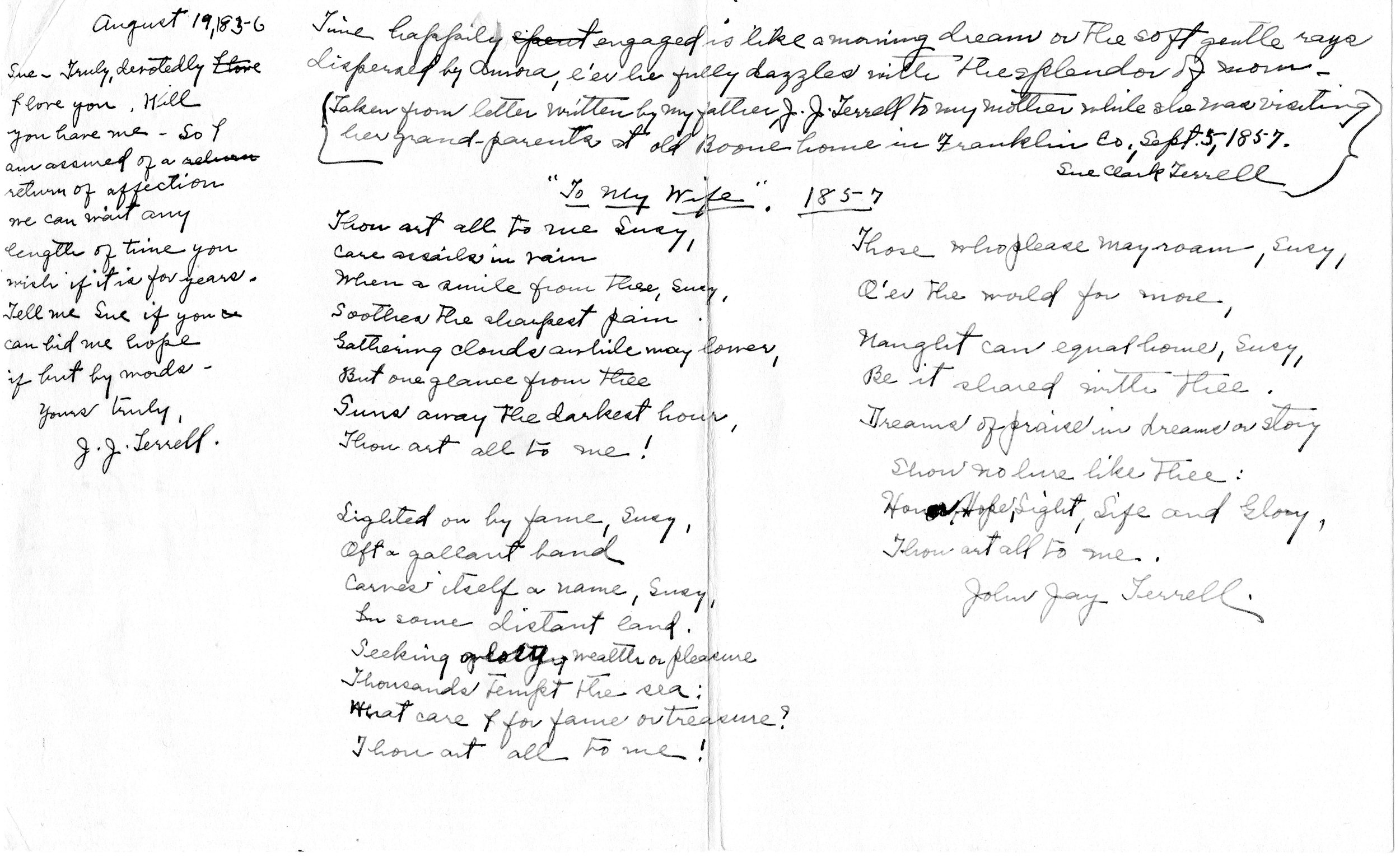

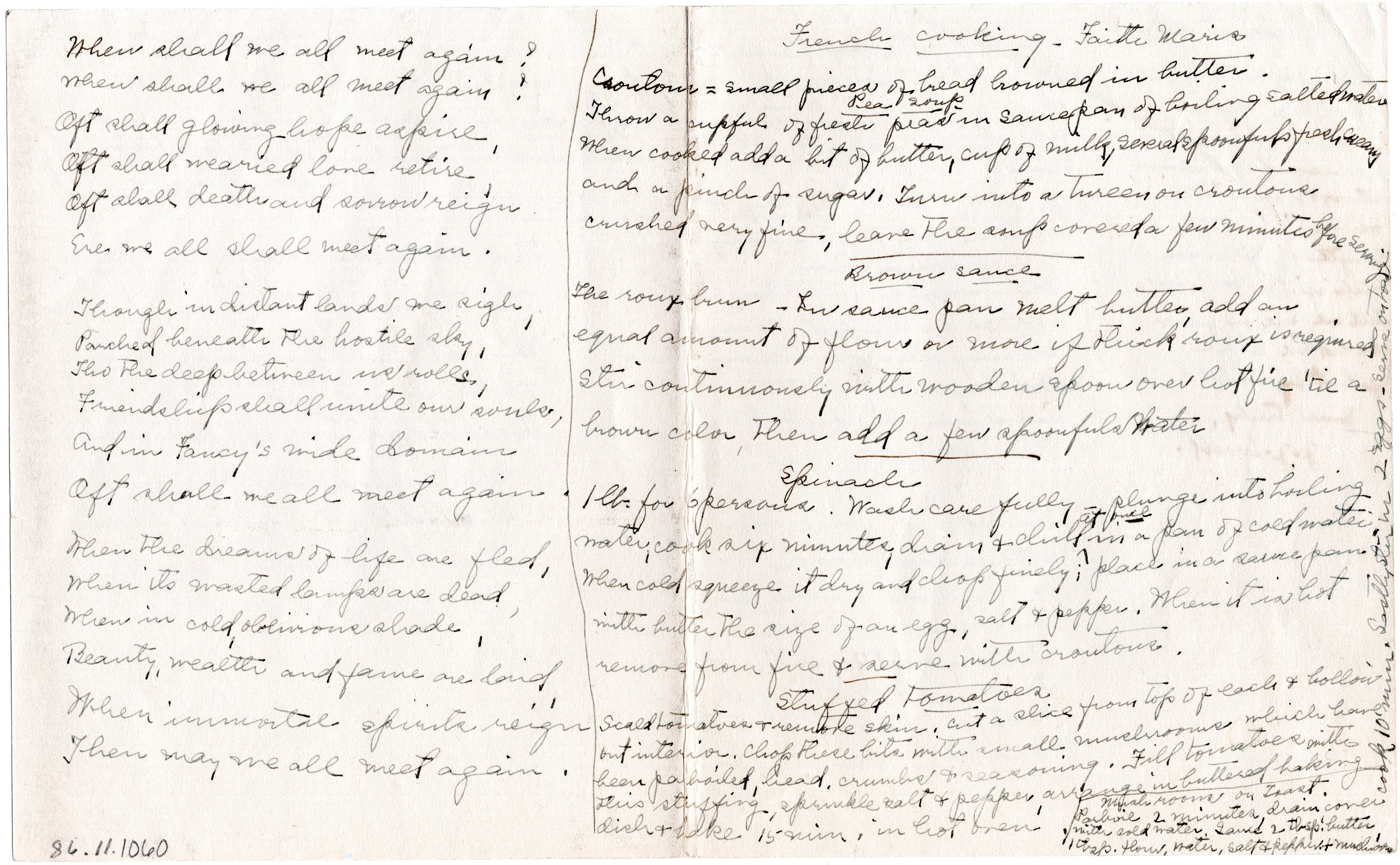

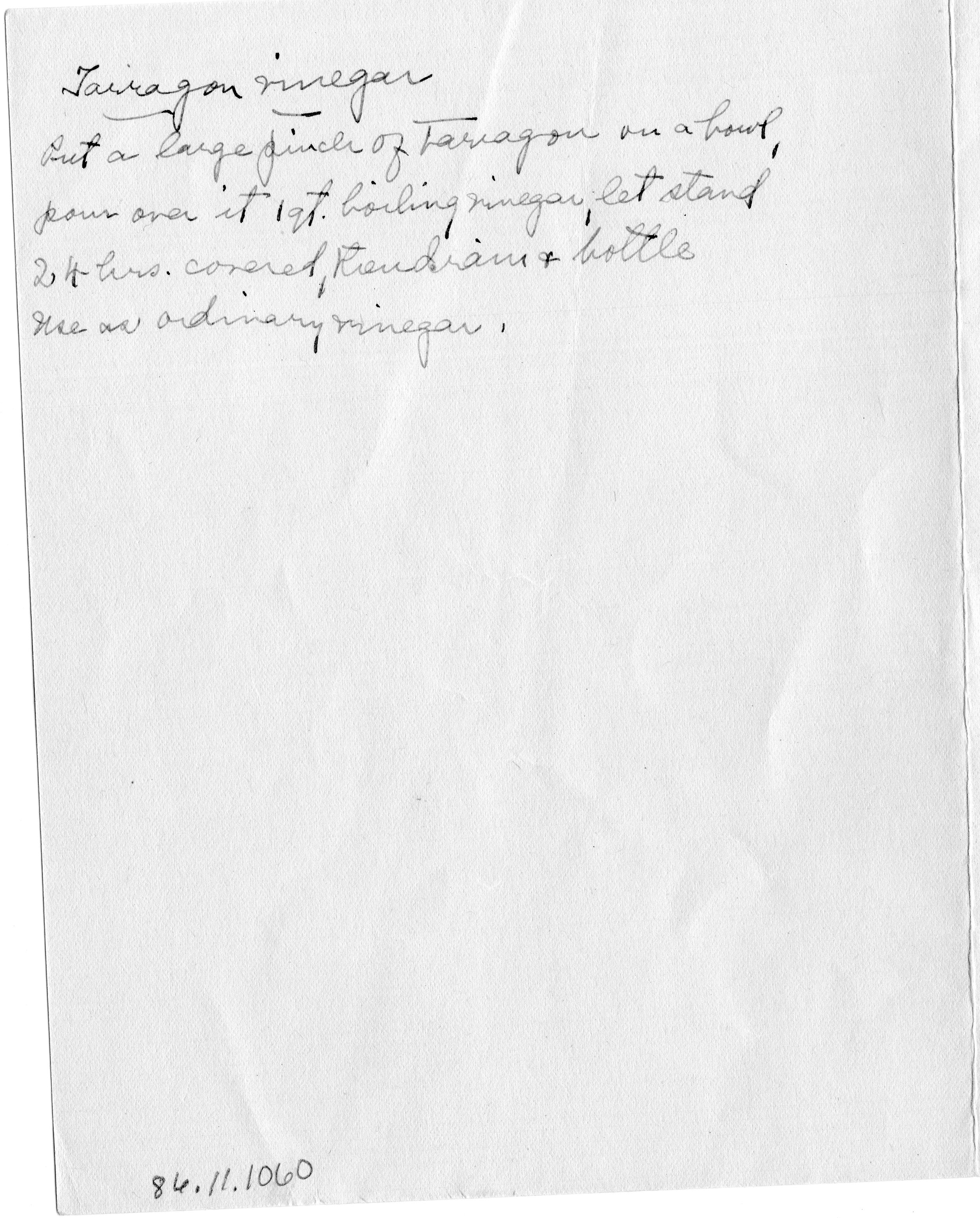

Dr. John J. Terrell was a local physician who wrote this poem for his wife Susan in 1857, the year they were married. The opposite side reads “French Cooking” with love notes scrolled alongside the recipe. Terrell later became a Civil War doctor and worked out of Old City Cemetery’s Pest House.

Portrait: Courtesy of Old City Cemetery

Letter: Gift of Dr. Ernest G. Scott, 86.11.1060

“Time happily s̶p̶e̶n̶t engaged is like a morning dream or the soft gentle rays dispersed by Aurora, e’er he fully dazzles with the splendor of morn.”

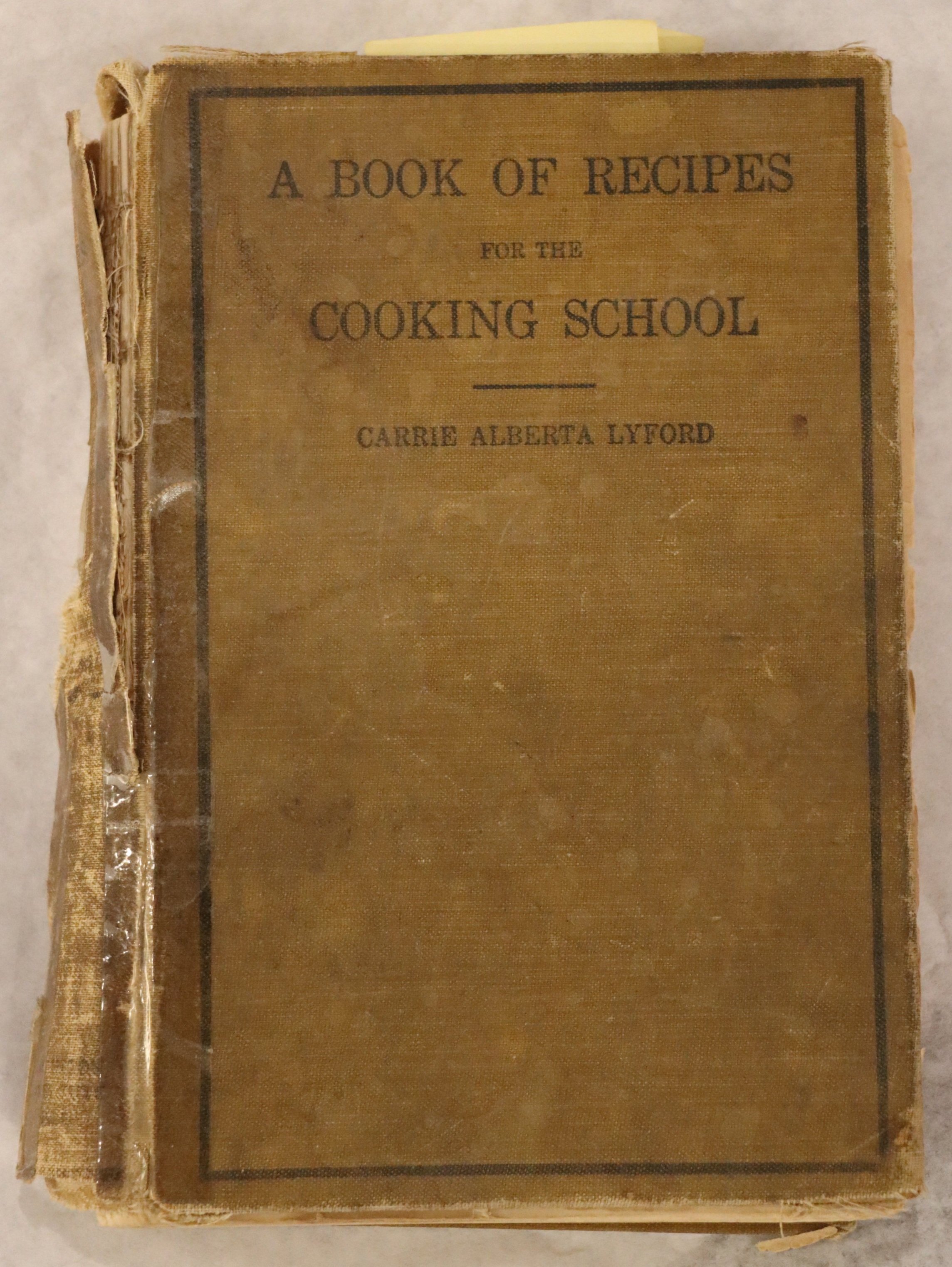

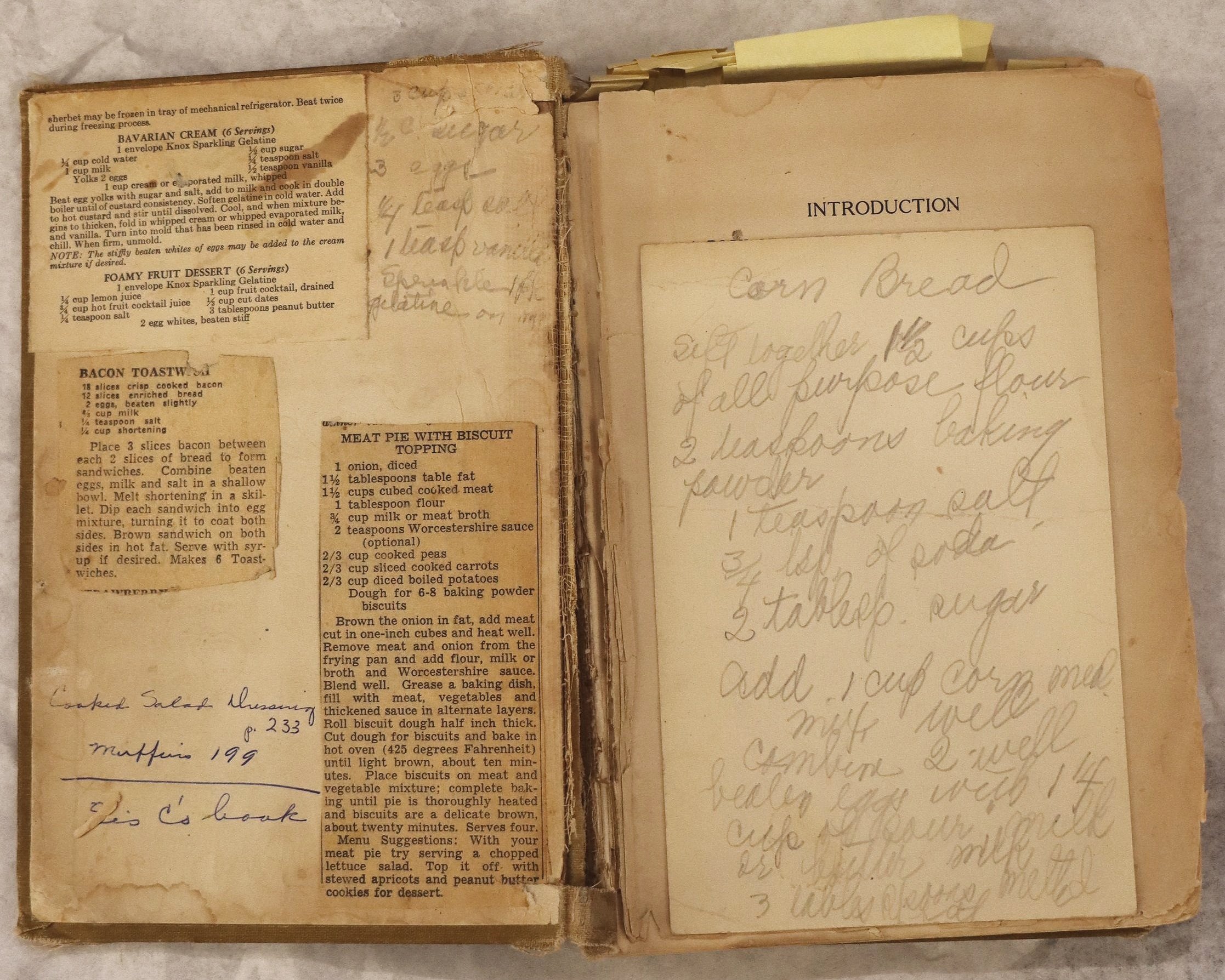

Amelia Perry Pride was an influential community leader in Lynchburg during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1880 she became one of the first Black women to be employed by the city’s public school system. She was a teacher and principal for more than three decades at the Polk Street, Payne, and Jackson Street Schools. Pride also was instrumental in incorporating home economics into the curriculum for Black students within the public school system.

Outside of her work as an educator, Pride opened a retirement home for formerly enslaved women who lived in poverty. It was called the “Dorchester Home” and was in operation for 10 years on Pierce Street. The women were taught sewing and quilting techniques and maintained the home.

In order to teach young girls and boys the “plainest form of industry,” she founded a free sewing school known as the “McKenzie Sewing School” in the Polk Street school building where she was principal. Later, in 1903, she opened the “Theresa Pierce Cooking School” for children on Madison Street. This was one of the books used in her schools.

Gift of Dr. Martin and Barbara Walton, III, 2019.65.2

Bettie Glover was born in 1872. She graduated from Lynchburg High School in 1891, which at the time was racially segregated. Black students attended a school on Jackson Street and white students attended school at the corner of 11th and Court Street. The locations of the segregated schools changed over the decades and would not be fully integrated until 1970.

After graduation Glover married Reverend Sandy Garland of Peaceful Baptist Church on Pierce Street and lived with him and their six children on Main Street.

Gift of Carolyn Brown, 2021.29.1

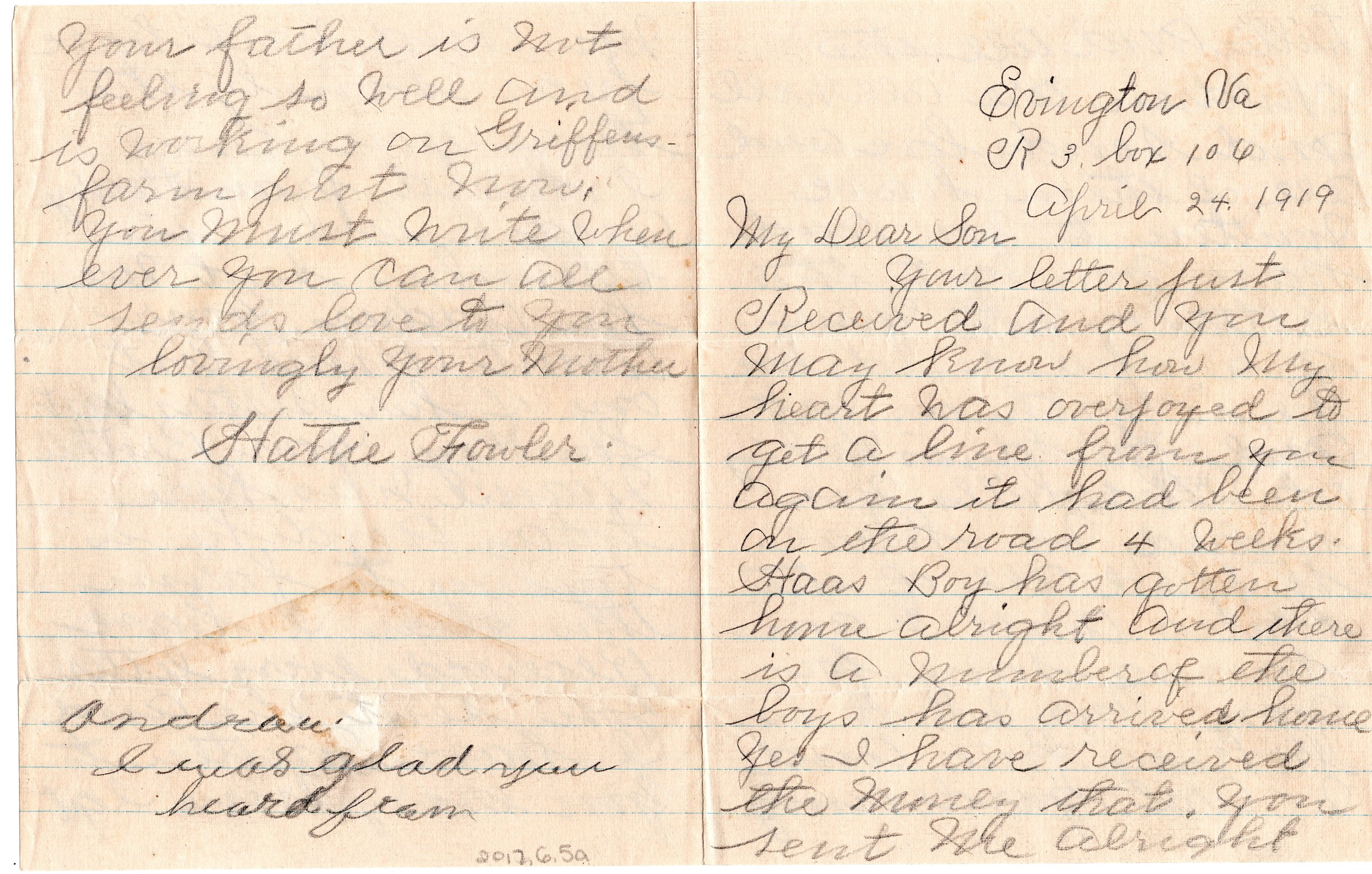

Royal Fowler was born in 1896. Before enlisting in the US Army in 1918 he worked as a road laborer. He became a member of the 808 Pioneer Infantry which was composed entirely of Black soldiers. They performed railroad construction, salvage work, and repaired damaged roads all while subject to enemy fire. While overseas, Fowler received letters and postcards from his family back home in the Lynchburg area. His collection includes not only correspondences, but also uniform items and photographs from his time in the service.

Portrait: Gift of Clinton Allen, 2017.6.3

Letter: Gift of Clinton Allen, 2017.6.5a

“Your letter just Received and you may know how my heart was overjoyed to get a line from you again it had been on the road 4 weeks.”

C.W. Seay was an educator and influential leader in Lynchburg. In 1970 he was elected to City Council and in 1974 was re-elected for a second term. Seay had the distinction of being the first African American on Lynchburg City Council since the 1880’s during Reconstruction. He held the position of vice-mayor and also served on the Transportation, Finance, Bridge Construction, and Drug Abuse Committees and was involved with many local organizations, including United Way, the Lynchburg Planning Commission, American Red Cross, United Negro College Fund, NAACP, Jackson Street United Methodist Church, and more.

In the 1974 election, he received over 6,000 votes, which was more than any other candidate that year. Based on his qualifications and public support, he expected to be elected by council as mayor. Instead, City Council elected incumbent Leighton Dodd, who came in fourth in the popular vote. Seay briefly considered stepping down from council, but decided against it. He chose not to run again and retired from council in 1978.

Frank Murray wrote this letter dated in 1976 to encourage Seay to run for another term.

Gift of C.W. Seay, 87.11.201

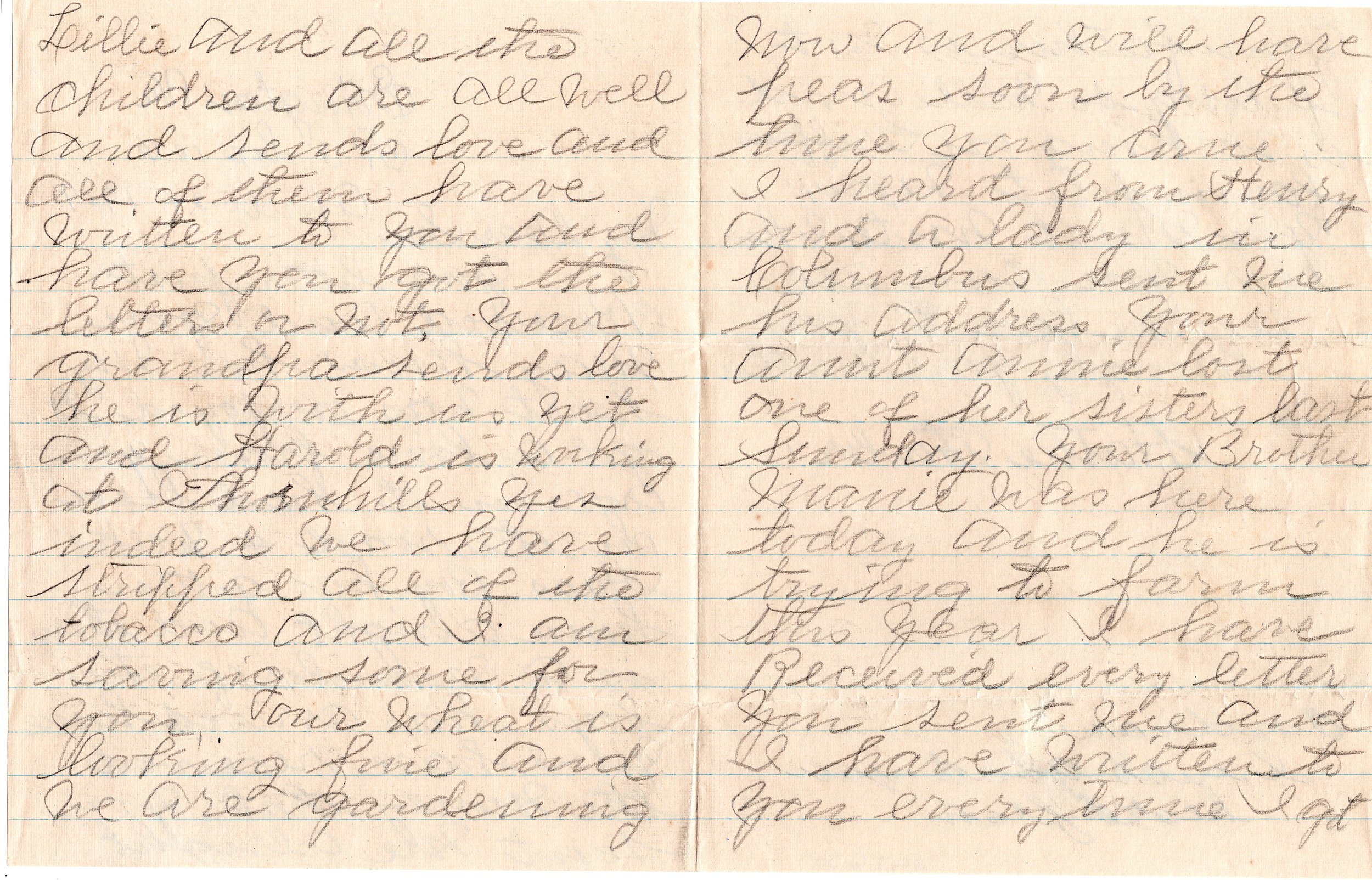

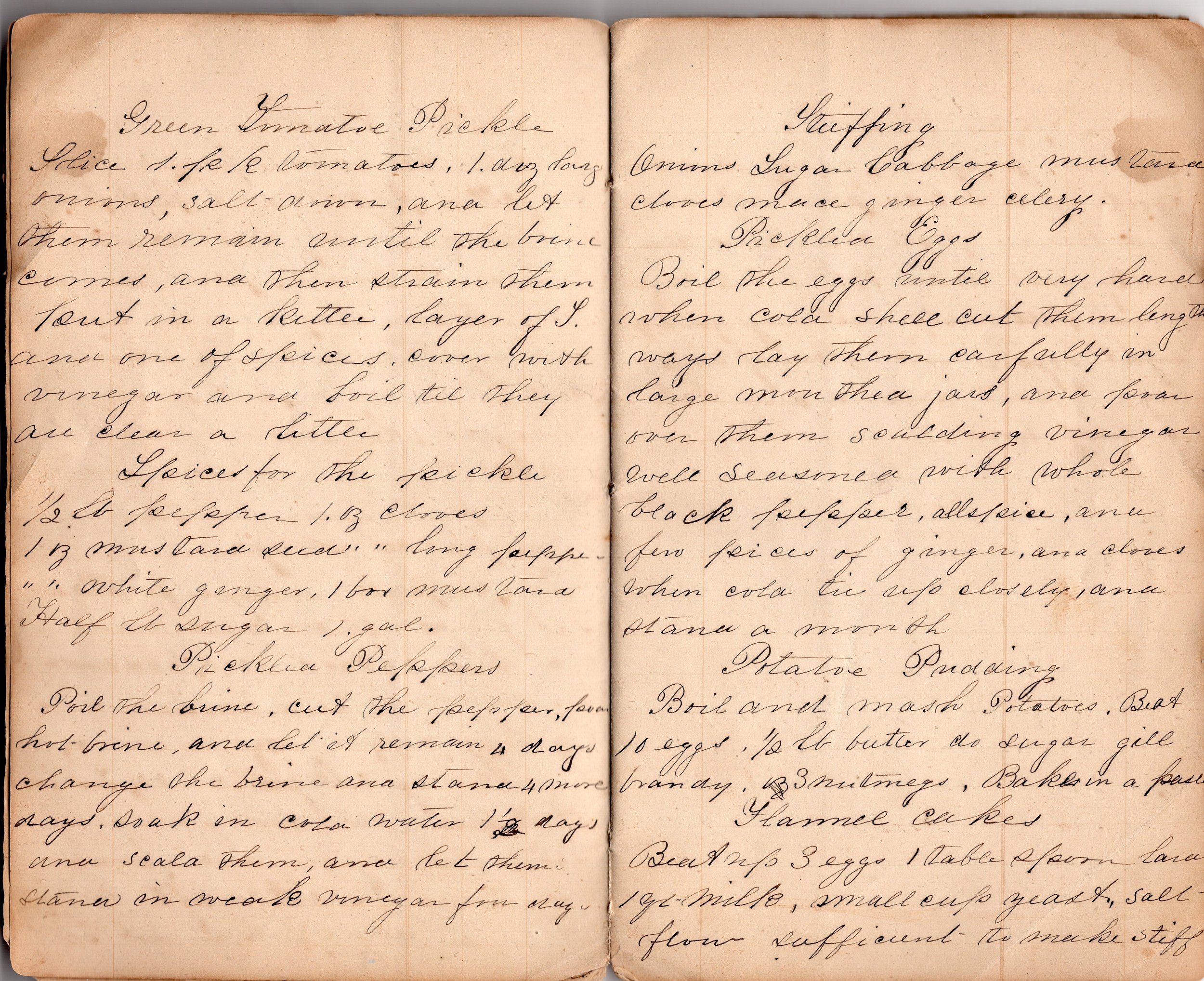

This recipe book dates from 1857 to 1919 and is inscribed J.W. Moore on the cover, but belonged to a woman named Liza. One of the recipes inside indicates it was from Mrs. N.R. Bowman who was married to a wealthy tobacconist. Recipes were often shared between friends and were copied from handwritten sources.

Gift of Ida B. Younger, 93.37.4

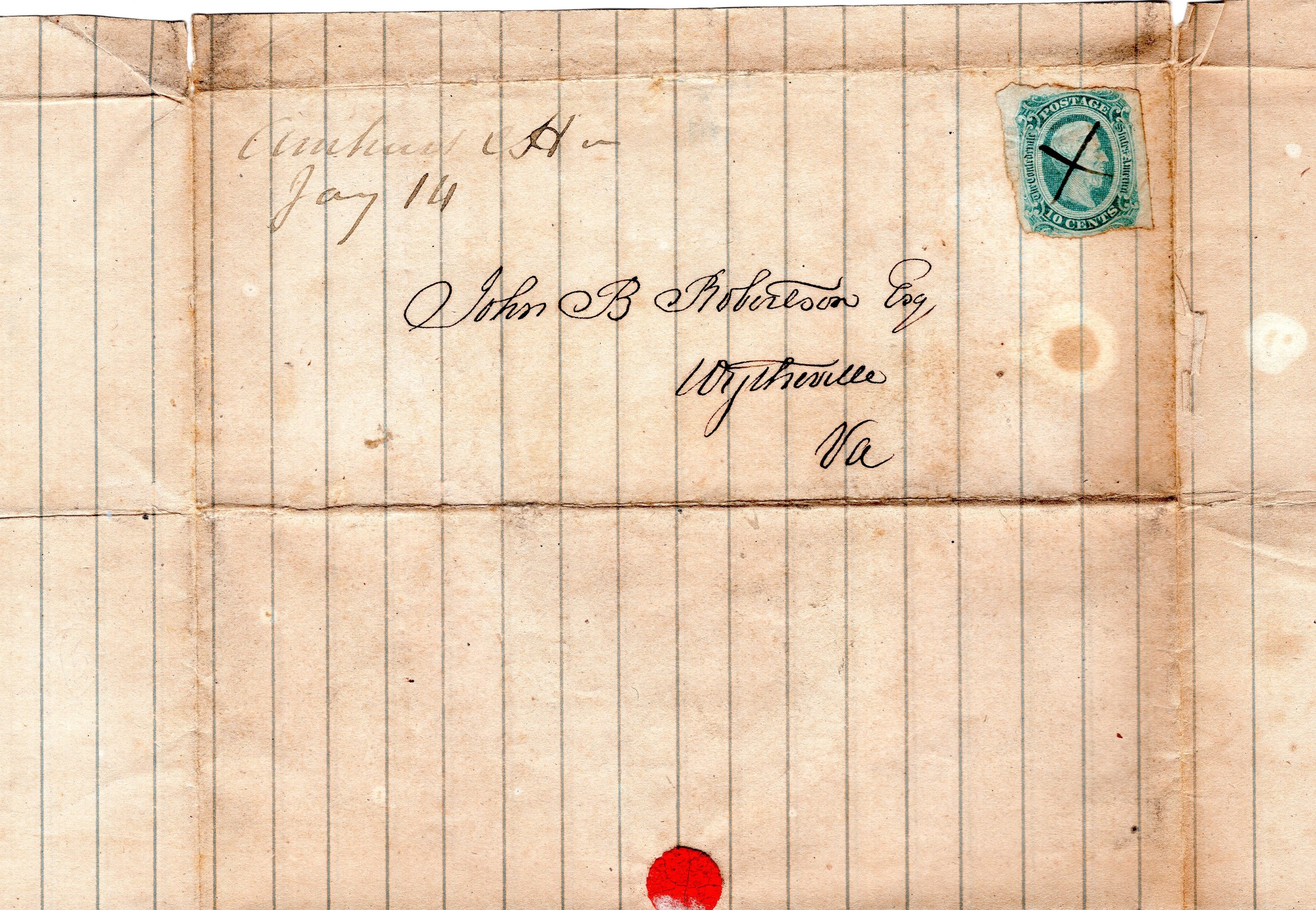

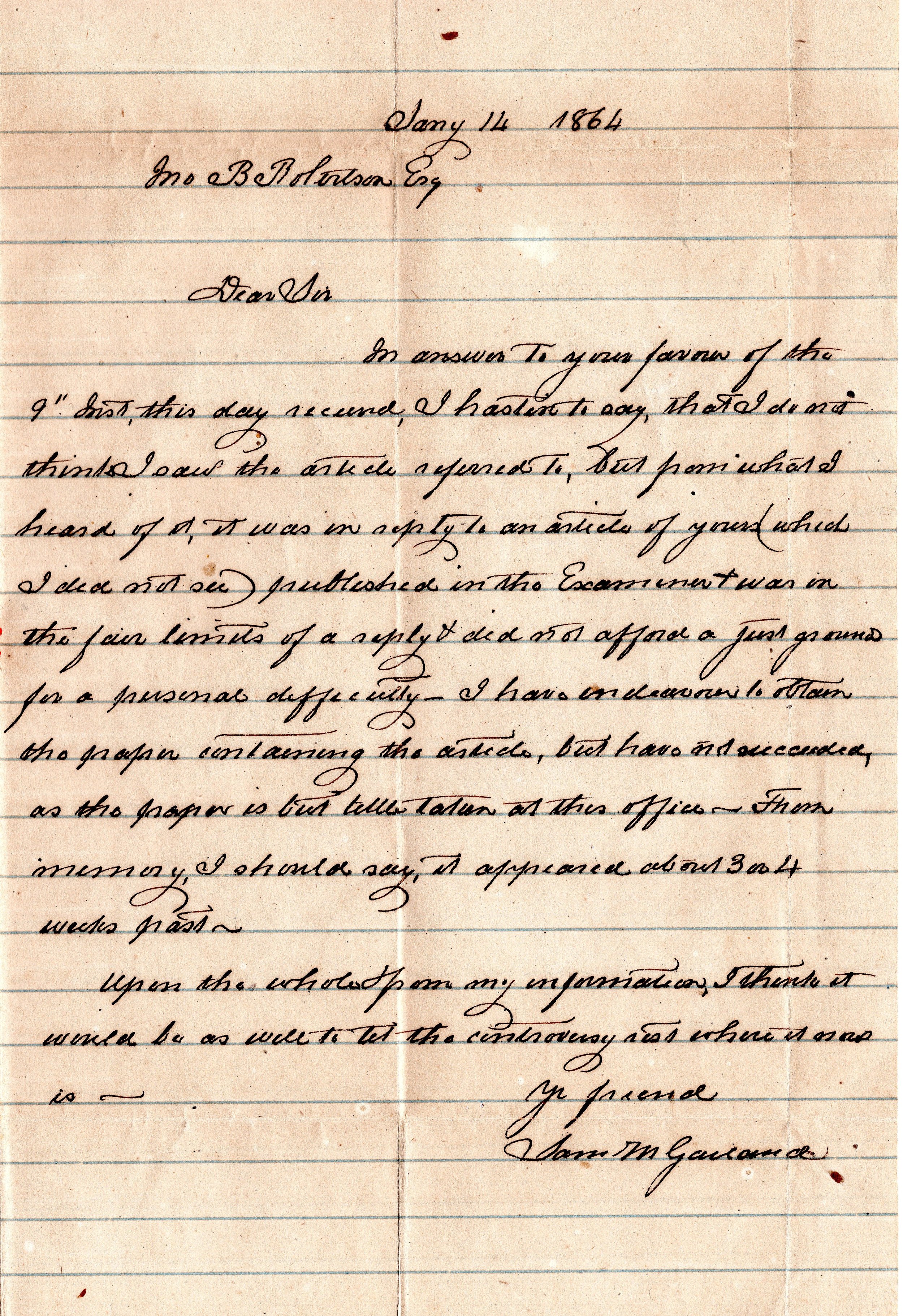

Whether a lawyer is drafting a letter or a legal document the language used is extremely formal. This letter was written during the Civil war on January 14, 1864 by Sam Garland, a lawyer in Amherst Court House, Virginia.

Gift of Dr. Robert Gardener, 2005.2.24

Legible handwriting may be read by others and is considered the art form of calligraphy. Calligraphy is essentially practical, but may range in variety all the way to graffiti. The handwritten recipes, notes in the margins of books, and letters of loved ones evoke heartfelt emotions. One of art’s many definitions!

Share Your History!

Does your family or neighborhood have any handwriting traditions? Do you know any local calligraphers? If so, we’d love to hear from you! The Lynchburg Museum System is actively seeking artifacts and archives to illustrate the full history of our city.

Call (434) 455-6226 or email museum@lynchburgva.gov